Mar. 18, 2024

A new study by Associate Professor Omar Isaac Asensio and a team of students in Georgia Tech’s School of Public Policy finds that federal housing policies accelerate energy efficiency participation among low- and moderate-income households — even when those policies don’t directly address energy efficiency.

The research, published in Nature Sustainability, shows how community development block grants from the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) generated an average of 5% to 11% energy savings in economically burdened households in Albany. The savings equate to the cost of roughly two months of groceries per household per year.

"These housing participants who didn't come in thinking about energy efficiency saved anywhere from $75 to $482 per year in energy bills," Asensio said. "Those are meaningful savings that really impact people. So, we ended up finding very significant hidden social benefits from these policies that were previously unknown."

https://youtu.be/eWqOFj9qRxw

The findings are surprising because HUD grants do not specifically target energy efficiency or sustainability measures in exchange for governmental assistance. Instead, they are given at the discretion of the local government to residents facing housing emergencies such as deteriorating roofs or broken HVAC systems in the hot summer. Because of the high amount of deferred maintenance in these homes, the fixes have a spillover effect of significantly reducing energy use — for example, by adopting more efficient technologies and bringing structures up to building codes — and saving money for people who receive them.

The multidisciplinary research team in Asensio’s Data Science & Policy Lab, including current and former Public Policy students Olga Churkina and Becky D. Rafter and industrial engineering alumna Kira E. O'Hare, also found that the cost-effectiveness of housing-based interventions rivals standalone energy efficiency policies, offering a promising alternative for reaching marginalized communities.

"For decades, we’ve struggled to get meaningful participation with conventional policies in these lower and moderate-income communities, including among renters and people in multi-family homes,” Asensio said. "Using housing block grants as an entry strategy to drive efficiency is an important policy innovation.”

With support from the National Science Foundation, ESRI, Inc., and the Georgia Smart Communities Challenge, Asensio and his co-authors spent nearly four years collecting, cleaning, and combining Albany's previously siloed city data into one community analytics repository. They linked records for 5.9 million utility bills per month from 2004 to 2019, allowing them to see long-run impacts of policy intervention, energy consumption, and payments by household — an uncommonly granular level of data.

"Overall, HUD-funded block grants in Albany reduced electricity use by 4.72 million kilowatt hours over the study period versus the control group," the researchers wrote. "The reduction in non-baseload emissions is equivalent to 3.70 million pounds of coal not being burned or the carbon sequestered by 3,695 acres of forest."

Asensio's research is timely because the Southeast has some of the country's highest energy-burdened households. In the U.S., spending over 6% of net income on energy is considered a burden. In Albany, renters' and homeowners' energy costs can surpass ten or even 20% of household budgets, Asensio said, and many housing applicants are elderly and on fixed incomes.

Unlike conventional energy initiatives that are reliant on self-selection, housing programs can provide a more equitable and localized strategy. That's because "most of the standalone policies for energy efficiency have two main outcomes," Asensio said. "First, the programs generally attract more affluent and informed homeowners, in which case, questions arise as to whether this might be a good use of public funds. Second, when these policies are restricted to certain income eligibility limits, we don't get enough participation from lower-income residents for a long list of reasons. So, reaching low- and moderate-income households has become a fundamental challenge."

In contrast, housing block grants naturally target a broader range of residents with high energy burdens and help circumvent the problem of low participation. Rather than trying to market an energy-saving offer to people who aren't interested or are distrustful of the government, HUD grants have long waiting lists.

"There are thousands and thousands of communities that look very much like Albany within and outside of major metro areas,” Asensio said. "This is a relatively untapped opportunity for driving energy efficiency within households who may not necessarily have an awareness of or interest in energy efficiency measures.”

The paper, “Housing Policies and Energy Efficiency Spillovers in Low and Moderate Income Communities,” was published online in Nature Sustainability on March 18. It is available at https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-024-01314-w. This work was partially supported by awards from the National Science Foundation (Award No. 1945332), ESRI, Inc., the Georgia Smart Communities Challenge, and the Institute for the Study of Business in Global Society at Harvard Business School.

News Contact

Di Minardi

Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts

Feb. 05, 2024

Faculty

Dylan Brewer, Daniel Dench, and Laura Taylor

Written by Sharon Murphy

About This Project

The Energy, Policy, and Innovation Center faculty affiliates Dylan Brewer, Daniel Dench, and Interim Director Laura Taylor published an article titled "Advances in Causal Inference at the Intersection of Air Pollution and Health Outcomes." The authors compare the methods used in the epidemiology literature with the causal inference framework used in economics in analyzing the effect of air pollution on health outcomes.

Determining the quality and accuracy of the evidence linking air pollution to human health has been a challenge for research in this area.

Each academic discipline has a unique lens through which they view and solve a problem, which may result in different conclusions being drawn from the same data. While studies that involve randomization across populations can provide evidence and are widely used in medical research, exposures to everyday air pollution cannot be randomized by a researcher.

Many existing studies exploring the health impacts of air pollution rely on establishing correlations between pollutants and health outcomes. However, correlations do not imply causation and can lead to bad policy. In this study, the EPICenter affiliates reviewed methodological contributions made by economists to determine if using statistical methods to the study of the health effects of air pollution can contribute to more robust and reliable findings.

To understand the difficulty researchers face, consider a typical air pollution study that collects health data of residents living near a pollution source, such as a coal-fired power plant. The data would be used to see if there is an increased incidence of adverse health outcomes such as asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, or cardiopulmonary disease. However, many factors can create a confounding effect on the final results if the researcher doesn’t take them into consideration. For instance, the power plant may have been built in a low-income location, or lower-income households may have moved near the power plant to take advantage of lower rent or property prices. This may conflate the effect of income and air pollution on health.

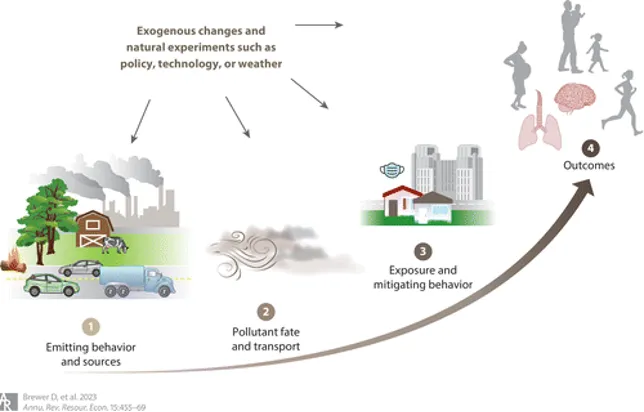

Simple schematic documenting the path of air pollution from emissions to outcomes. This review discusses the challenges of measuring how emissions of pollutants (step 1) disperse through the air (step 2) to become eventual exposures (step 3) and health outcomes (step 4).

Economists promote the use of natural experiments to overcome confounding factors. Natural experiments mimic familiar laboratory experiments. For instance, in the power plant example, random variation in wind direction would result in some households being randomly more exposed to air pollution, regardless of income. By taking advantage of this randomization, researchers can compare differences in a particular health outcome between those more exposed and less exposed, while overcoming confounding effects such as income, and move one step closer toward improving our understanding of the relationship between air pollution and adverse health outcomes.

The authors conclude by emphasizing the need for creating multidisciplinary teams, including economists, air-quality modelers, and public health and medical researchers. “While one may not think of economists as a natural contributor to this line of research, the analytical framework honed by economists over decades can contribute important expertise to the design of these types of studies,” Taylor concluded, “and result in better evidence for policymakers.”

Read more: https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-resource-101722-081026

News Contact

Priya Devarajan | SEI Communications Program Manager

Authored by: Sharon Murphy, Strategic Energy Institute

Jan. 29, 2024

The study of energy is multidimensional and can be approached through disciplines such as economics and public policy, engineering, science, and even architecture and urban planning. The Energy, Policy, and Innovation Center at Georgia Tech (EPICenter) seeks to create bridges between faculty and students whose work may be enhanced through complementary research or knowledge in disciplines across campus and has named the first class of faculty affiliates in the EPICenter program.

Thirteen Georgia Tech faculty have been appointed as EPICenter Affiliates, representing the study of energy through the lenses of economics, public policy, electrical engineering, civil and environmental engineering, and industrial and systems engineering. The affiliates will act as an informal advisory committee to help guide EPICenter and connect Georgia Tech energy researchers to each other and to policy and decision-makers throughout the Southeast.

EPICenter Interim Director Laura Taylor envisions the Faculty Affiliate program to lead to more enrichment opportunities for students, and more awareness of the research intersections of energy technology, economics, and public policy.

About Energy at Georgia Tech

The Georgia Institute of Technology is renowned for its world-class academic programs such as engineering, business, computer science, and city and regional planning. There is a depth of excellence at Georgia Tech that few universities can match thanks in large part to the faculty, many of whom are the foremost experts in their fields. U.S. News & World Report recently ranked Georgia Tech third in the nation for energy and fuels research.

News Contact

Priya Devarajan || Communications Program Manager | SEI

Oct. 18, 2023

The Georgia Tech Energy, Policy, and Innovation Center, in partnership with Clean Cities Georgia, Atlanta Gas Light, Georgia Chamber of Commerce, Georgia Power, and Southface Institute, hosted the 2023 Clean Cities Georgia Transportation Summit in September. The event highlighted the successes and benefits of all forms of clean transportation in Georgia and across the nation and provided an opportunity for more than 100 attendees to network and build public-private partnerships. The summit also honored the 30th anniversary of the Department of Energy’s (DOE) National Clean Cities Network, and Clean Cities Georgia, which was the first coalition founded in 1993.

Tim Lieuwen, executive director of the Georgia Tech Strategic Energy Institute, Ian Skelton, natural gas vehicles director of Atlanta Gas Light, and Frank Norris, executive director of Clean Cities Georgia, provided the welcome and opening remarks followed by a panel of executives from UPS, Chevron, and the DeKalb County Fleet Management who discussed the benefits of adopting clean fuels for businesses.

“I am excited that Georgia Tech continues to play an integral role in convening industry and community in the local region and helping to build strong relationships that will positively impact the regional and national energy landscape,” said Lieuwen, Regents’ Professor and David S. Lewis Jr. Chair in the Daniel Guggenheim School of Aerospace Engineering. “Events like this tap into the regional expertise within academia, businesses, nongovernmental organizations, and research facilities, which speaks to the vision of EPICenter.”

The daylong summit consisted of panels discussing use cases for alternate fuels available in the market: natural gas/renewable natural gas, electric vehicle (EV) applications, propane and renewable propane, biofuels and sustainable aviation fuels, and current and future hydrogen applications. Panelists shared processes and considerations that led to the successful implementation of alternate fuels within their organization, including choosing locations, procurement, state and regional policies, incentives, effects on the community, improvements in current processes, reduced carbon footprint, and scalability while shifting from fossil to alternate fuels.

Panelists from Cobb, DeKalb, and Henry counties shared successful implementations of alternate fuel vehicles in their respective localities that included propane, renewable natural gas and EVs and showcased some of their alternate fuel vehicles during the summit. Workforce development and infrastructure concerns included training new electricians, aging line men in the region, and future proofing charging stations. Transformer supply chain issues were also brought to the forefront during discussions throughout the day.

Representatives from the Office of Energy Efficiency and Renewable Energy and the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency spoke to the audience on how to work with their respective agencies to get federal funding in this area. The event ended with a 30-year review of Clean Cities Georgia, a nonprofit that started as the first initiative of the DOE to focus on strategies to reduce petroleum consumption in transportation. There are now nearly 100 coalitions across the country.

The event was part of National Drive Electric Week, which took place during the last week of September. Presentations and other details from the summit can be accessed through the 2023 Clean Cities Georgia summit webpage.

News Contact

Priya Devarajan || Research Communications Program Manager

Jan. 20, 2023

Inclusivity and understanding past policies and their effects on underserved and marginalized communities must be part of urban planning, design, and public policy efforts for cities.

An international coalition of researchers — led by Georgia Tech — have determined that advancements and innovations in urban research and design must incorporate serious analysis and collaborations with scientists, public policy experts, local leaders, and citizens. To address environmental issues and infrastructure challenges cities face, the coalition identified three core focus areas with research priorities for long-term urban sustainability and viability. Those focus areas should be components of any urban planning, design, and sustainability initiative.

The researchers found that the core focus areas included social justice and equity, circularity, and a concept called “digital twins.” The team — which consists of 13 co-authors and scholars based in the U.S., Asia, and Europe — also provided guidance and future research directions for how to address these focus areas. They detailed their findings in the Journal of Industrial Ecology, published in January 2023.

“Climate change has certainly increased the amount and intensity of extreme weather events and because of that, it makes our decision making today critical to the manner in which our economy and our day to day lives can operate,” said Joe F. Bozeman III, the lead author and an assistant professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Civil and Environmental Engineering. He is also the director of Tech’s Social Equity & Environmental Engineering Lab and has a courtesy appointment in the School of Public Policy. “Our quality of life can be negatively affected if we don't make good decisions today.”

Three core areas of focus to achieve urban sustainability

The researchers’ first core focus area, justice and equity, addresses innovations and trends that disproportionately benefit middle and high-income communities. Trends like IoT, “smart cities,” and the urban “green movement” are part of a broader push by cities to become more sustainable and resilient. But communities of color and low-income neighborhoods — the same areas often home to environmental contaminations, infrastructure challenges, and other hazards — have often been overlooked.

The researchers’ findings showed a consistent trend with marginalized communities across several countries, including Canada, the Netherlands, India, and South Africa. They call for mandatory equity analyses which incorporate the experiences and perspectives of these marginalized communities, and, more importantly, ensure members of those communities are actively engaged in decision-making processes.

“Planning, professional, and community stakeholders,” the researchers write in the paper, “should recognize that working together gets cities closer to harmonizing the technological and social dimensions of sustainability.”

The second focus area, circularity, addresses resource consumption of staple commodities including food, water, and energy; the waste and emissions they generate; and the opportunities to increase conservation of those resources by boosting efficiencies.

“What we mean by circularity is basic reuse, remanufacturing, and recycling efforts across the entire urban system — which not only includes cities and under resourced areas within those cities — but also rural communities that supply and take resources from those city hubs,” Bozeman said. The idea is aligned with the circular economy concept which addresses the need to move away from the resource-wasteful and unsustainable cycle of taking, making, and throwing away.

Instead, the researchers argue, cities should look for ways to improve efficiency and maximize local resource use. That has potential benefits not only for urban areas, but rural communities, too. One example, Bozeman said, is the Lifecycle Building Center in Atlanta. It takes old building supplies and sells them locally for reuse.

“By doing that, they’re at the beginning stages of creating an economic system, a regional engine where we share resources between cities and rural areas,” he said. “We can start creating an economic framework, not only where both sides can make money and get what they need, but something that can actually turn into a sustainable economic engine without having to rely on another state or another country's import or export economic pressures.”

To strengthen circularity and make it more robust, the researchers call for more expansive metrics beyond measuring recycling rates and zero waste efforts, to include other parts of the supply chain that may yield new ideas and solutions.

The third focus area, digital twins, addresses the development of automated technologies in smart buildings and infrastructure, such as traffic lights to respond to weather and other environmental factors.

“Let's say there's a heavy rain event and that the rainwater is being stored into retainment,” said Bozeman. “An automated system can open another valve where we can store that water into a secondary support system, so there's less flooding, and that can happen automatically, if we utilize the concept of digital twins.”

Creating a new urban planning model

The research came about as part of the mission of the Sustainable Urban Systems Section of the International Society for Industrial Ecology, which aims to be a conduit for scientists, engineers, policymakers, and others who want to marry environmental concerns and economic activity. Bozeman is a board member of the Sustainable Urban Systems Section.

“In that role, part of we do is set a vision and foundation for how other researchers should operate within the city and urban system space,” he said.

For urban sustainability, engineers and policy makers must come to the table and make collective decisions around social justice and equity, circularity, and the digital twins concepts.

“I think we're at a really critical decision point when it comes to engineers and others being able to do work that is forward looking and human sensitive,” said Bozeman. “Good decision making involves addressing social justice and equity and understanding its root causes, which will enable cities to create solutions that integrate cultural dynamics.”

CITATION: Joe F. Bozeman III, Shauhrat S. Chopra, Philip James, Sajjad Muhammad, Hua Cai, Kangkang Tong, Maya Carrasquillo, Harold Rickenbacker, Destenie Nock, Weslynne Ashton, Oliver Heidrich, Sybil Derrible, Melissa Bilec. “Three research priorities for just and sustainable urban systems: Now is the time to refocus.” (Journal of Industrial Ecology, January 2023)

News Contact

Péralte C. Paul

peralte.paul@comm.gatech.edu

404.316.1210

Jun. 30, 2022

The second class of Brook Byers Institute for Sustainable Systems (BBISS) Graduate Fellows has been selected. The BBISS Graduate Fellows Program provides graduate students with enhanced training in sustainability, team science, and leadership in addition to their usual programs of study. Each two-year fellowship is funded by a generous gift from Brook and Shawn Byers and is additionally guided by a Faculty Advisory Board. The students apply their skills and talents, working directly with their peers, faculty, and external partners on long-term, large team, sustainability relevant projects. They are also afforded opportunities to organize and host seminar series, develop their professional networks, publish papers and draft proposals, and develop additional skills critical to their professional success and future careers leading research teams.

The 2022 class of Brook Byers Institute for Sustainable Systems Graduate Fellows are:

- Oliver Chapman - Ph.D. student, School of Public Policy, Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts

- Megan Conville - Ph.D. student, School of City and Regional Planning, College of Design

- Carlos Fernandez - Ph.D. student, George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering, College of Engineering

- Sarah Roney - Ph.D. student, School of Biological Sciences

- Olianike Olaomo - Ph.D. student, School of History and Sociology, Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts

- Vishal Sharma - Ph.D. student, School of Interactive Computing, College of Computing

The Faculty Advisory Board for the BBISS Graduate Fellows is composed of the faculty who submitted the students' nominations. Nominations for Class III of the BBISS Graduate Fellows program will open in the Spring 2023. It is expected that 6 to 8 scholars will be selected for next year’s group.

The Faculty Advisory Board for the inaugural class are:

Updates and outcomes will be posted to the BBISS website as the project progresses. Additional information is available at https://research.gatech.edu/sustainability/grad-fellows-program.

News Contact

Brent Verrill, Research Communications Program Manager

Apr. 20, 2022

The rising sea levels along Georgia’s Savannah coast and an uptick in more severe storms during hurricane season are bellwethers to looming ecological challenges stemming from climate change.

Ongoing research to study sea level rise led by Georgia Tech researchers, a coalition of universities, Savannah and Chatham County government leaders, and local community groups is creating what could be a national model for coastal regions across the country facing similar challenges.

Launched in 2018 with a Georgia Smart Communities Challenge Grant, the data collected from the sea level sensors is used to inform city and county planners and emergency responders on resource deployment following major weather events.

Now in its fourth year, the sea sensor project is now slated to receive $5 million from Congress. It is secured by U.S. Sens. Jon Ossoff and Raphael Warnock, and U.S. Rep. Earl L. “Buddy” Carter to expand the network of sensors — currently 50 are deployed off Chatham County’s coast — to blanket Georgia’s 11-county coastal region.

“With this new funding, we are recognizing a new phase of our project which has evolved,” said Kim Cobb, former director of Georgia Tech’s Global Change Program and a professor who studies climate, oceanography, and weather in the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences.

Cobb and Russell J. Clark, senior research scientist in the School of Computer Science at Georgia Tech’s College of Computing, co-lead the project. Allen Hyde, assistant professor in the School of History and Sociology in Georgia Tech’s Ivan Allen College of Liberal Arts, leads a National Science Foundation project focused on youth disaster resilience as part of the effort.

The funding will support expansion of building out more hyperlocal flood forecasting models, resilience planning tools for underserved communities, and further development of a K-12 education curriculum, paid internships, and other workforce development programs.

Georgia Tech and its partners — which includes Savannah State University, the University of Georgia, and the University of South Carolina — is using these low-cost sensors to gain real-time data that over time will help inform the policies on infrastructure design and retrofitting, Cobb said. It will also further expand first responders and emergency planners’ ability to forecast extreme rainfall and storm surge events on a neighborhood-by-neighborhood specific basis.

“It's going to translate into a saved lives and saved infrastructure,” Cobb said.

A National Model

Hub researchers say the data being collected from the sensors and additional information gleaned from the sensor expansion has immediate applications in terms of flood disasters and hurricanes. Those findings over the long-term could also help frame the national dialogue and help inform policy as leaders in Washington shape it to tackle rising sea levels and climate change.

The award is part of a broader federal push, including a $12 billion funding package, to help Georgia and other states along the Eastern Seaboard, as well as the West and Gulf coasts, develop resiliency and flooding plans and protocols to mitigate damage from future floods.

Cobb said this new funding allows the Hub to further efforts in its research that further expands education and workforce development — particularly in underserved minority communities — as components of the broader strategy.

“Our project started out anchored on the sensors and trying to provide real-time data to emergency planners and emergency response responders, but it’s no longer just a small team of people who are interested in sensors or physical scientists, engineers and researchers on the science and technology side,” she said, explaining the research team of some 30 people also includes policy and planning experts, along with community advocates.

“We're trying to think about solutions in the context of history, geography, — the history of people, cultures, and economies down on the coast,” Cobb said. “There’s no waving a magic wand and making this all right, especially for the most vulnerable communities.”

Community Voice

In broad terms, the project touches flooding, infrastructure, property, and pollution. But this newer phase brings in aspects that go beyond scientific modeling of risk, said Dean Hardy, an assistant professor in the University of South Carolina’s Department of Geography.

It’s what he calls the “human dimension” phase.

“There are disaster plans, there's resiliency plans, and there's community level thinking. But what we need is systemic change,” said Hardy, whose research expertise is in geography and integrative conservation, which marries preservation and social and community goals with public policy.

“So, what I hope partially comes out of this is not just a bunch of scientific publications or better scientific understanding of these issues, but capacity-building with community organizations that leads to the capacity for self-determination.”

That acknowledgement is important to marginalized communities, said Dawud Shabaka, interim director of Harambee House, in Savannah. The organization, which is involved in the sensor project, promotes and advocates for civic engagement from the coastal city’s Black residents and youth.

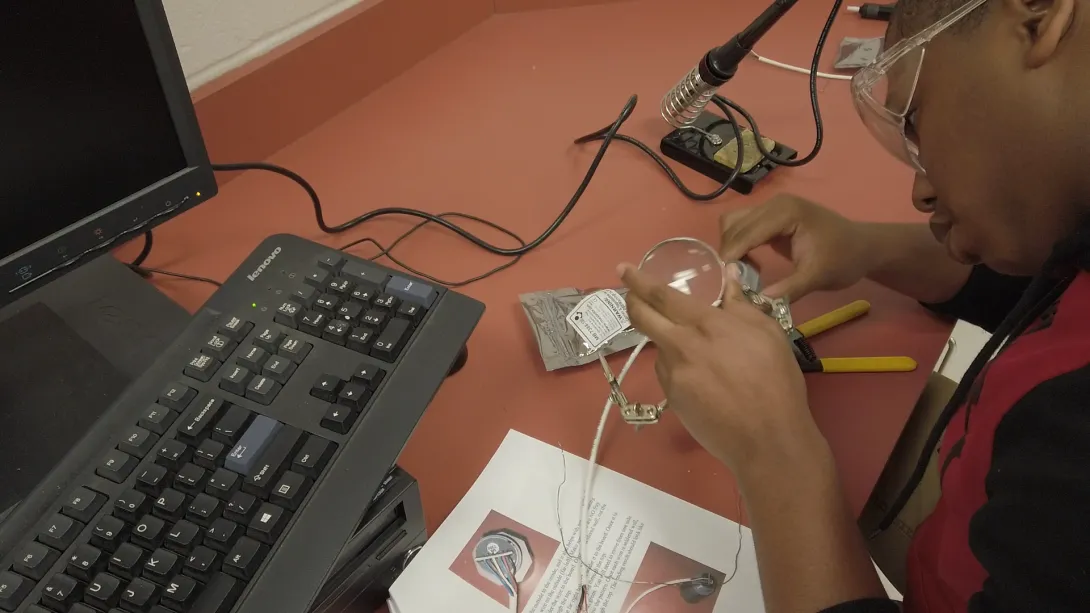

Shabaka noted that the engagement component, particularly local high school and middle school students working on the sensors and coding, has allowed the participants to see themselves not only as budding scientists, but as future community leaders.

“When you’re dealing with or managing or mitigating an issue that’s affecting society, it’s got to involve research and dialogue with the community. This project is allowing us to recognize that the community themselves are the subject matter experts,” said Shabaka. “Having the students involved at an early age, benefits society as a whole and lets them know that the work they’re doing is having a much wider impact. This is the type of community engagement that needs to happen to make people feel like they’re worthwhile.”

News Contact

Péralte C. Paul

peralte.paul@comm.gatech.edu

404.316.1210

Jan. 21, 2022

This country’s semiconductor chip shortage is likely to continue well into 2022, and a Georgia Tech expert predicts that the U.S. will need to make major changes to the manufacturing and supply chain of these all-important chips in the coming year to stave off further effects.

That includes making more of these chips here at home.

Madhavan Swaminathan is the John Pippin Chair in Electromagnetics in the School of Electrical and Computer Engineering. He also serves as director of the 3D Systems Packaging Research Center.

As an author of more than 450 technical publications who holds 29 patents, Swaminathan is one of the world’s leading experts on semiconductors and the semiconductor chips necessary for many of the devices we use every day to function.

“Almost any consumer device that is electronic tends to have at least one semiconductor chip in it,” Swaminathan explains. “The more complicated the functions any device performs, the more chips it is likely to have.”

Some of these semiconductor chips process information, some store data, and others provide sensing or communication functions.

In short, they are crucial in devices from video games and smart thermostats to cars and computers.

Our current shortage of these chips began with the Covid-19 pandemic. When consumers started staying at home and car purchases took a downward turn, chip manufacturers tried to shift to make more chips for other goods like smartphones and computers.

But Swaminathan explains that making that kind of switch is not simple. Entire production operations have to be changed. The chips are highly sensitive and can be damaged by static electricity, temperature variations, and even tiny specks of dust. The manufacturing environments must be highly regulated, and changes in the process can add months.

The pandemic highlighted another challenge with the semiconductor chip industry, according to Swaminathan.

“There’s a major shortage of companies making chips,” he says. “If you look worldwide, there are maybe four or five manufacturers making 80-90% of these chips and they are located outside of the United States.”

This creates supply chain hiccups with the raw supplies needed to make these chips as well. Add in the fact that many of these companies only design their chips – they don’t manufacture them directly.

“American consumers use 50% of the world’s chips,” Swaminathan says, which creates a serious challenge when the overwhelming majority of those chips are manufactured in other nations.

In the short term, the costs of the chip shortage is being passed on to the consumer. We see this directly with products like PlayStations and Xboxes that are more and more expensive and harder to purchase when the chips necessary for the consoles to function are in short supply.

Beyond 2022, Swaminathan says we need to work to revitalize the industry domestically.

“We need to bring more manufacturing back to the United States,” he says. “The U.S. government has recognized the importance of this semiconductor chip shortage and is trying to address the issue directly.”

That means investing in new plants to manufacture the chips, but America's journey toward chip self-sufficiency will continue to be a work in progress.

“This is a cycle,” Swaminathan explains. “But this is probably the first time where it has had such a major effect in so many different industries.”

But consumers can take direct action on their own in the coming year. “Reduce the number of times you purchase or upgrade electronic devices like phones and cars,” he says. “Then it becomes just a supply problem, not a demand and supply problem.”

Dec. 03, 2020

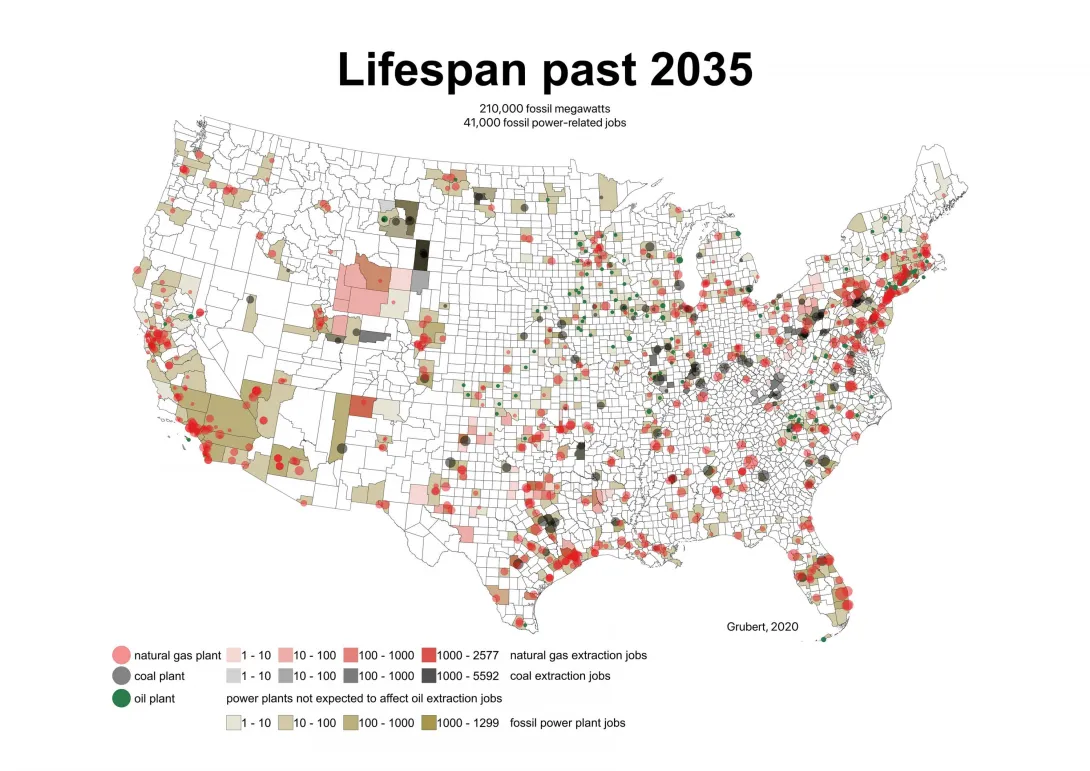

Decarbonizing U.S. electricity production will require both construction of renewable energy sources and retirement of power plants now operated by fossil fuels. A generator-level model described in the Dec. 4 issue of the journal Science suggests that most fossil fuel power plants could complete normal lifespans and still close by 2035 because so many facilities are nearing the end of their operational lives.

Meeting a 2035 deadline for decarbonizing U.S. electricity production, as proposed by the incoming U.S. presidential administration, would eliminate just 15% of the capacity-years left in plants powered by fossil fuels, says the article by Emily Grubert, a Georgia Institute of Technology researcher. Plant retirements are already underway, with 126 gigawatts of fossil generator capacity taken out of production between 2009 and 2018, including 33 gigawatts in 2017 and 2018 alone.

“Creating an electricity system that does not contribute to climate change is actually two processes — building carbon-free infrastructure like solar plants, and closing carbon-based infrastructure like coal plants,” said Grubert, an assistant professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Civil and Environmental Engineering. “My work shows that because a lot of U.S. fossil fuel plants are already pretty old, the target of decarbonization by 2035 would not require us to shut most of these plants down earlier than their typical lifespans.”

Of U.S. fossil fuel-fired generation capacity, 73% (630 out of 840 gigawatts) will reach the end of its typical lifespan by 2035; that percentage would reach 96% by 2050, she says in the Policy Forum article published in Science. About 13% of U.S. fossil fuel-fired generation capacity (110 gigawatts) operating in 2018 had already exceeded its typical lifespan.

Because typical lifespans are averages, some generators operate for longer than expected. Allowing facilities to run until they retire is thus likely insufficient for a 2035 decarbonization deadline, the article notes. Closure deadlines that strand assets relative to reasonable lifespan expectations, however, could create financial liability for debts and other costs. The research found that a 2035 deadline for completely retiring fossil fuel-based electricity generators would only strand about 15% (1,700 gigawatt-years) of capacity life, along with about 20% (380,000 job-years) of direct power plant and fuel extraction jobs that existed in 2018.

In 2018, fossil fuel facilities operated in 1,248 of 3,141 counties, directly employing about 157,000 people at generators and fuel extraction facilities. Plant closure deadlines can improve outcomes for workers and host communities — providing additional certainty, for example, by enabling specific advance planning for things like remediation, retraining for displaced workers, and revenue replacements.

“Closing large industrial facilities like power plants can be really disruptive for the people who work there and live in the surrounding communities,” Grubert said. “We don't want to repeat the damage we saw with the collapse of the steel industry in the 1970s and ’80s, where people lost jobs, pensions, and stability without warning. We already know where the plants are, and who might be affected. Using the 2035 decarbonization deadline to guide explicit, community grounded planning for what to do next can help, even without a lot of financial support.”

Planning ahead will also help avoid creating new capital investment that may not be needed long-term. “We shouldn't build new fossil fuel power plants that would still be young in 2035, and we need to have explicit plans for closures both to ensure the system keeps working and to limit disruption for host communities,” she said.

Underlying policies governing the retirement of fossil fuel-powered facilities is the concept of a “just transition” that ensures material well-being and distributional justice for individuals and communities affected by a transition from fossil to non-fossil electricity systems. Determining which assets are “stranded,” or required to close earlier than expected, is vital for managing compensation for remaining debt or lost revenue, Grubert said in the article.

CITATION: Emily Grubert, “Fossil electricity retirement deadlines for a just transition” (Science, 2020). https://science.sciencemag.org/content/370/6521/1171

Research News

Georgia Institute of Technology

177 North Avenue

Atlanta, Georgia 30332-0181 USA

Media Relations Contact: John Toon (404-894-6986) (jtoon@gatech.edu)

Writer: John Toon

News Contact

John Toon

Research News

(404) 894-6986

Nov. 30, 2020

When one or more coronavirus vaccines receives FDA emergency use authorization, it will launch a public health and logistics initiative unlike any in U.S. history.

Hundreds of millions of doses will have to distributed nationwide and kept cold until healthcare professionals can administer not one, but two doses to each person. And enough skeptical members of the population will have to be persuaded to receive the vaccine to slow virus transmission.

Beyond those challenges, the distribution effort will have to adapt to unexpected and uneven demand; accommodate recipients who may not return on time for a second dose; train hundreds of thousands of staff from clinics, pharmacies, doctor’s offices, and hospitals; prioritize serving high-risk groups first while encouraging others to wait — all while under tremendous pressure to get the much-anticipated vaccines into use as case counts and the death toll continue rising.

“Time is of the essence because the virus is already so widespread,” said Pinar Keskinocak, the William W. George Chair and professor in the H. Milton Stewart School of Industrial and Systems Engineering (ISyE) and director of the Center for Health and Humanitarian Systems at the Georgia Institute of Technology. “With the pressure on our timeline, knowledge of how quickly the disease is spreading, and the broad U.S. and global need, I can’t think of a comparable public health initiative that has ever been undertaken.”

Shipping and Keeping Hundreds of Millions of Doses Cold

Three vaccines, produced by Moderna, Pfizer and its German partner BioNTech, and Oxford-AstraZeneca, are expected to be available first. The Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine will need to be kept ultra-cold — minus 94 degrees Fahrenheit — on its journey to individual Americans. The Moderna drug won’t have such demanding conditions, but both it and the Pfizer vaccine will tax the existing “cold chain” that keeps vaccines and other temperature-sensitive products in a narrow range of conditions during transport and storage.

The Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine will have much less stringent requirements and faster ramp-up in capacity, though early testing suggests its efficacy may be lower than the others. That will create tradeoffs between efficacy versus access and speed in distribution.

Plans already exist to get the vaccines from manufacturers to the states, each of which has developed its own distribution plan. Keskinocak worries mostly about “last mile” plans — getting the vaccines to where they will be injected — and getting individuals to those locations.

“Access is going to be a challenge,” she said. “You may be able to get it to locations where it can be distributed, but you have to make sure the people who really need the vaccine can easily access those locations.”

Cold chain transportation, tracking, tracing, and storage already exist in most areas, but refrigeration could be challenging for rural areas that may be at the end of the chain, especially for the vaccine requiring very cold temperatures beyond the capability of freezers found in most doctor’s offices and clinics. And cold can sometimes be too cold, Keskinocak said.

“We often think about keeping it cold, but sometimes it may be too cold, which is not good. It’s not just whether the temperature exceeded the required level, but also whether it went below that. It is important to keep the vaccine exactly at the required temperature level.”

Pfizer has developed a shipping container that includes a temperature tracking device — and 50 pounds of dry ice to maintain the right temperature during transit. Because it is contained in small vials and the liquid vaccine is diluted for use, the overall volume being shipped will be relatively small, limiting the number of packages that will be moved and stored, Keskinocak noted.

Ultimately, the cold chain may play a significant role in vaccine effectiveness. Currently, the vaccines being produced by Pfizer/BioNTech and Moderna are reported to have a higher efficacy than the Oxford-AstraZeneca vaccine — but only if they can be maintained at the proper temperatures. The timing, magnitude, and duration of temperature fluctuations during transport and before administration could affect that in ways that may be difficult to assess.

“Our current modeling shows that a vaccine that is less effective but that can be distributed more quickly and more widely might work better in some settings than a more effective vaccine, thereby reducing the total number of infections in the population,” Keskinocak said.

If You Build It, Will They Come?

Expectations are that the nation is hungry for a vaccine to escape the horrors of Covid-19. But a recent Gallup survey shows that only 58% of respondents said they planned to receive the vaccine when it becomes available. Boosting that percentage will require a massive communications effort to overcome vaccine reluctance and concerns fueled by the uneven nature of the U.S. pandemic response.

“If we can get the vaccine to locations where people can access it, and we have the necessary syringes, supplies, and PPE, as well as the healthcare staff to administer the injections, it’s not clear that people will come to receive it in large enough numbers,” Keskinocak said. “That’s one major component missing from a lot of the plans that I see at the state level.”

The communications program will have to run in parallel to the vaccine distribution, and they have to be coordinated so that supply meets demand.

“Public health communication and dissemination of information at the right time and in the right language is going to be at least as important and challenging as the logistics of distributing the vaccine,” Keskinocak said. “Communication is going to shape demand to a large extent. If one is more effective than the other, we will have a mismatch between demand and supply.”

Different demographic populations have different levels of trust for medicine in general and vaccines in particular, she said, so communications campaigns will have to focus on issues of concern to those groups. Unexpected variations in vaccine demand caused by these concerns could also create logistical uncertainties.

“We can try to forecast demand, and ship supplies to those locations,” she said. “But historically, we have seen that demand can exceed supply in one location while inventory builds up in another location. We need to avoid this situation of unmet demand and unused vaccine.”

Another issue will be the two doses necessary for the vaccine. The second dose must be received within a narrow range of time for the two-dose vaccine to be effective. Should a second dose be reserved for every person receiving a first dose, or should the goal be to get as many doses out as possible?

“Some people may never show up to be vaccinated, while others will receive the first dose, but may not come back for the second dose,” she said.

Getting the Program Started

The first available doses will likely go to healthcare workers and first responders who are on the front lines of battling Covid-19. That is expected to be the easier part of vaccination logistics, and the lessons learned there should help with the much more massive vaccination campaign for high-risk individuals and the general public.

As vaccine production and distribution capacity ramp up, other groups will be next in line. While distributing small batches as manufacturers produce it can create some supply challenges, that also allows the system to more easily adjust to unexpected demand.

Even though distributing and administering vaccines is something the U.S. healthcare system does routinely, the size and timeline of this project are unprecedented, Keskinocak noted.

Beyond the logistical and communications needs, the vaccination program will also have a strong information technology component. Administration will likely be by appointment, and each injection will have to be reported to a vaccine registry to provide a record of which vaccines people have received and when.

Vaccinating People Who May Already Be Immune

It’s estimated that the number of reported Covid-19 cases may be just 10% of the actual number of infections in the U.S. Assuming recovery from the virus confers immunity for some period of time means there may be quite a few people who don’t actually need the vaccine right away to be protected. But there are currently no plans to determine whether recipients are already immune before they receive the vaccine.

“There are a lot of people out there who have some level of immunity to the coronavirus,” Keskinocak said. “The plans I’ve seen don’t include the serological testing that would be needed to identify people with some level of immunity, which could be around 30% of the population by the time the vaccine gets out to the general public.”

Testing for immune antibodies could be done ahead of the vaccination program, but that would create an extra step in a process that is already quite complicated. Healthcare systems such as the U.S. Department of Veterans Affairs or certain private insurance plans could include that step, especially if vaccine supplies lag behind demand.

“The big complexity is timing,” she said. “Once vaccines become available, you’ll want to deliver them as quickly as possible to as many people as possible in a very short time frame.”

Annual vaccination campaigns for the seasonal flu set ambitious goals for the population levels they want to reach, but the time challenges will be much greater for the coronavirus vaccine.

“The seasonal flu vaccine becomes available months before the virus spreads broadly, so we have quite a bit of time to administer it before we get into the peak of the flu season,” she said. “We have been in the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic for several months now. We are really late in the game, so we don’t have the luxury of time.”

Keskinocak is cautiously optimistic that the challenges will ultimately be addressed.

“There are certainly still lots of unknowns,” she said. “But the state plans I have seen look reasonable from a supply chain standpoint. Some of the decisions will be made once the states receive the vaccine, and exactly how they do it will be somewhat up to the local jurisdictions. There are still many things that need to be decided to make this unprecedented initiative live up to its goals.”

Research News

Georgia Institute of Technology

177 North Avenue

Atlanta, Georgia 30332-0181 USA

Media Relations Contact: John Toon (404-894-6986) (jtoon@gatech.edu)

Writer: John Toon

News Contact

John Toon

Research News

(404-894-6986)

Pagination

- Previous page

- 2 Page 2

- Next page