Jul. 07, 2025

Researchers at Georgia Tech’s School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering (ChBE) have developed a promising approach for removing carbon dioxide (CO₂) from the atmosphere to help mitigate global warming.

While promising technologies for direct air capture (DAC) have emerged over the past decade, high capital and energy costs have hindered DAC implementation.

However, in a new study published in Energy & Environmental Science, the research team demonstrated techniques for capturing CO₂ more efficiently and affordably using extremely cold air and widely available porous sorbent materials, expanding future deployment opportunities for DAC.

Harnessing Already Available Energy

The research team – including members from Oak Ridge National Laboratory in Tennessee and Jeonbuk National University and Chonnam National University in South Korea – employed a method combining DAC with the regasification of liquefied natural gas (LNG), a common industrial process that produces extremely cold temperatures.

LNG, which is a natural gas cooled into a liquid for shipping, must be warmed back into a gas before use. That warming process often uses seawater as the source of the heat and essentially wastes the low temperature energy embodied in the liquified natural gas.

Instead, by using the cold energy from LNG to chill the air, Georgia Tech researchers created a superior environment for capturing CO₂ using materials known as “physisorbents,” which are porous solids that soak up gases.

Most DAC systems in use today employ amine-based materials that chemically bind CO2 from the air, but they offer relatively limited pore space for capture, degrade over time, and require substantial energy to operate effectively. Physisorbents, however, offer longer lifespans and faster CO₂ uptake but often struggle in warm, humid conditions.

The research study showed that when air is cooled to near-cryogenic temperatures for DAC, almost all of the water vapor condenses out of the air. This enables physisorbents to achieve higher CO₂ capture performance without the need for expensive water-removal steps.

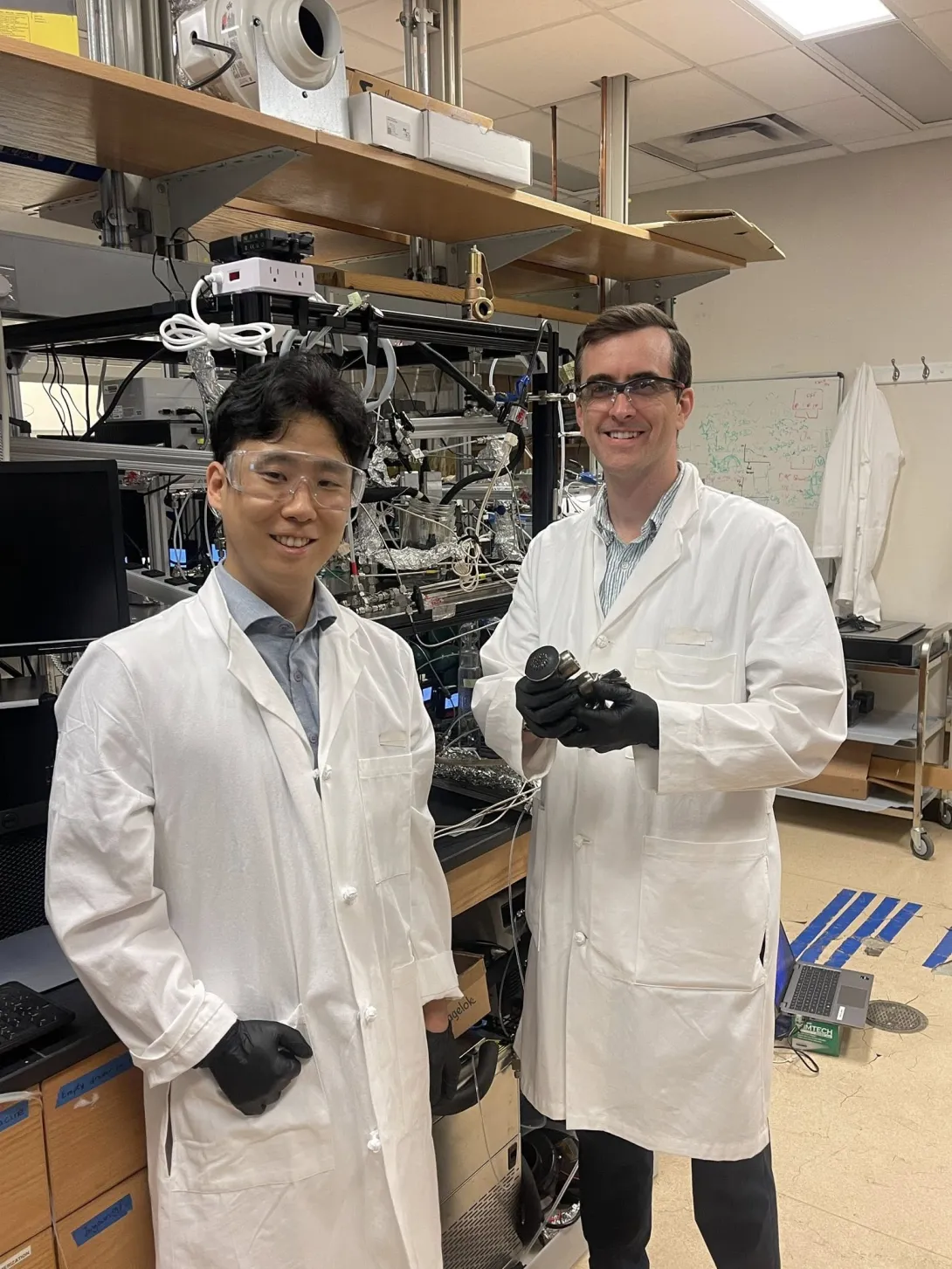

“This is an exciting step forward,” said Professor Ryan Lively of ChBE@GT. “We’re showing that you can capture carbon at low costs using existing infrastructure and safe, low-cost materials.”

Cost and Energy Savings

The economic modeling conducted by Lively’s team suggests that integrating this LNG-based approach into DAC could reduce the cost of capturing one metric ton of CO₂ to as low as $70, approximately a threefold decrease from current DAC methods, which often exceed $200 per ton.

Through simulations and experiments, the team identified Zeolite 13X and CALF-20 as leading physisorbents for this DAC process. Zeolite 13X is an inexpensive and durable desiccant material used in water treatment, while CALF-20 is a metal-organic framework (MOF) known for its stability and CO2 capture performance from flue gas, but not from air.

These materials showed strong CO₂ adsorption at -78°C (a representative temperature for the LNG-DAC system) with capacities approximately three times higher than those found in amine materials that operate at ambient conditions. They also released the captured and purified CO₂ with low energy input, making them attractive for practical use.

“Beyond their high CO2 capacities, both physisorbents exhibit critical characteristics such as low desorption enthalpy, cost efficiency, scalability, and long-term stability, all of which are essential for real-world applications,” said lead author Seo-Yul Kim, a postdoctoral researcher in the Lively Lab.

Leveraging Existing Infrastructure

The study also addresses a key concern for DAC: location. Traditional systems are often best suited for dry, cool environments. But by leveraging existing LNG infrastructure, near-cryogenic DAC could be deployed in temperate and even humid coastal regions, greatly expanding the geographic scope of carbon removal.

“LNG regasification systems are currently an untapped source of cold energy, with terminals operating at a large scale in coastal areas around the world,” Lively said. “By harnessing even just a portion of their cold energy, we could potentially capture over 100 million metric tons of CO₂ per year by 2050.”

As governments and industries face increasing pressure to meet net-zero emissions goals, solutions like LNG-coupled near-cryogenic DAC offer a promising path forward. The next steps for the team include continued refinement of materials and system designs to ensure performance and durability at larger scales.

“This is an exciting example of how rethinking energy flows in our existing infrastructure can lead to low-cost reductions in carbon footprint,” Lively said.

The study also demonstrated that an expanded range of materials could be employed for DAC. While only a small subset of materials can be used at ambient temperatures, the number that are viable grows substantially at near-cryogenic temperatures.

“Many physisorbents that were previously dismissed for DAC suddenly become viable when you drop the temperature,” said Professor Matthew Realff, co-author of the study and professor at ChBE@GT. “This unlocks a whole new design space for carbon capture materials.”

Citation: Seo-Yul Kim, Akriti Sarswat, Sunghyun Cho, MinGyu Song, Jinsu Kim, Matthew J. Realff, David S. Sholl, and Ryan P. Lively, “Near-Cryogenic Direct Air Capture using Adsorbents,” Energy & Environmental Science, 2025.

News Contact

Brad Dixon, braddixon@gatech.edu

May. 27, 2025

Space researcher. Materials scientist. Entrepreneur. And Yellow Jacket. The only thing missing on Jud Ready’s resume is “astronaut.” Not for lack of trying, though. Ready had hoped earning his bachelor’s, master’s, and doctoral degrees in materials science and engineering at Georgia Tech would lead him to a spot in NASA’s Astronaut Corps. Instead, it’s led him to the Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI), where his passion for space is alive and well.

1. What about space fascinates you?

It all goes back to my dad being interested in space. In first grade, we went to a how-to-use-the-library class, and I came across a book about the Mercury and Apollo astronauts. I checked it out and renewed it over and over again. I eventually finished it in second grade. So, I’ve had a lifelong commitment since then to space.

2. What drew you to engineering?

I grew up in Chapel Hill. In that same first grade class, we went to the University of North Carolina chemistry department. My mom is really into roses, and they froze a rose in liquid nitrogen then smashed it on the table. It broke into a million bits, and I was like, “What?!” The ability of science to solve the unknown grabbed me. And I had a series of very good science teachers — Mr. Parker in fifth grade, in particular. Then I took a soldering class in high school. We built a multimeter that I still have and still use, and various other things. And I suddenly discovered and started exploring engineering. Plus, I just like making things.

3. How did your career change from hoping to be an astronaut to being an accomplished materials engineer?

When I started looking at colleges, that was my primary interest: What school would help me become an astronaut the quickest. I applied to Georgia Tech as an aerospace engineer, but was admitted as an undecided engineering candidate instead. It was the best thing that could have happened. Later, I got hired as an undergrad by a professor who was doing space-grown gallium arsenide on the Space Shuttle. Ultimately, they offered me a graduate position. I accepted, because I knew you needed an advanced degree to be an astronaut — and for a civilian, a Ph.D. in a relevant career such as materials science.

I applied so many times to be an astronaut — every time they opened a call from 1999 until just a few years ago. Never got in. But I was successful at writing proposals and teaching. So I started doing space vicariously through my students, writing research proposals on energy capture, such as solar cells; energy storage, such as super capacitors; and energy delivery like electron emission. They’re all enabled by engineered materials.

4. What makes Georgia Tech and GTRI a key contributor to the future of humans and science in space?

Georgia Tech offers us so many unfair advantages over our competition. The equipment we’ve got. The students. You’ve got the curiosity-driven basic research coupled with the GTRI applied research model. We’ve had VentureLab and CREATE-X. Now we’ve got Quadrant-i to foster spinout companies from research.

5. One of your solar cell technologies is headed to the Smithsonian National Air & Space Museum. What is it?

Early in my career, we developed a way to texture thin film photovoltaics to allow for light trapping. Inverted pyramids are etched into silicon wafer-type solar cells so a photon of light has a chance to hit different surfaces and get absorbed. But thin film solar cells typically don’t etch well. I thought we could use carbon nanotubes to form a scaffolding, a structure like rebar. It’s mechanically reinforcing, but also electrically conductive. We coat the thin film solar cell material over the carbon nanotube arrays. You’ve got these towers, and you get this photon pinballing effect. Most solar cells perform best when perpendicular to the sun, but with mine, off angles are preferred. That’s great for orbital uses, because the faces and solar panels of spacecraft are frequently off-angle to the sun. And then you don’t have the complexity of mechanical systems adjusting the solar arrays. So, we got funding to demonstrate these solar cells on the International Space Station three times, and those are some of the cells we provided to the Smithsonian.

News Contact

Joshua Stewart (jstewart@gatech.edu)

Assistant Director of Communications,

College of Engineering, Georgia Tech

Apr. 28, 2025

Origami — the Japanese art of folding paper — could be at the next frontier in innovative materials.

Practiced in Japan since the early 1600s, origami involves combining simple folding techniques to create intricate designs. Now, Georgia Tech researchers are leveraging the technique as the foundation for next-generation materials that can both act as a solid and predictably deform, “folding” under the right forces. The research could lead to innovations in everything from heart stents to airplane wings and running shoes.

Recently published in Nature Communications, the study, “Coarse-grained fundamental forms for characterizing isometries of trapezoid-based origami metamaterials,” was led by first author James McInerney, who is now a NRC Research Associate at the Air Force Research Laboratory. McInerney, who completed the research while a postdoctoral student at the University of Michigan, was previously a doctoral student at Georgia Tech in the group of study co-author Zeb Rocklin. The team also includes Glaucio Paulino (Princeton University), Xiaoming Mao (University of Michigan), and Diego Misseroni (University of Trento).

“Origami has received a lot of attention over the past decade due to its ability to deploy or transform structures,” McInerney says. “Our team wondered how different types of folds could be used to control how a material deforms when different forces and pressures are applied to it” — like a creased piece of cardboard folding more predictably than one that might crumple without any creases.

The applications of that type of control are vast. “There are a variety of scenarios ranging from the design of buildings, aircraft, and naval vessels to the packaging and shipping of goods where there tends to be a trade-off between enhancing the load-bearing capabilities and increasing the total weight,” McInerney explains. “Our end goal is to enhance load-bearing designs by adding origami-inspired creases — without adding weight.”

The challenge, Rocklin adds, is using physics to find a way to predictably model what creases to use and when to achieve the best results.

Deformable solids

Rocklin, a theoretical physicist and associate professor in the School of Physics at Georgia Tech, emphasizes the complex nature of these types of materials. “If I tug on either end of a sheet of paper, it's solid — it doesn’t separate,” he explains. “But it's also flexible — it can crumple and wave depending on how I move it. That’s a very different behavior than what we might see in a conventional solid, and a very useful one.”

But while flexible solids are uniquely useful, they are also very hard to characterize, he says. “With these materials, it is often difficult to predict what is going to happen — how the material will deform under pressure because they can deform in many different ways. Conventional physics techniques can't solve this type of problem, which is why we're still coming up with new ways to characterize structures in the 21st century.”

When considering origami-inspired materials, physicists start with a flat sheet that's carefully creased to create a specific three-dimensional shape; these folds determine how the material behaves. But the method is limited: only parallelogram-based origami folding, which uses shapes like squares and rectangles, had previously been modeled, allowing for limited types of deformation.

“Our goal was to expand on this research to include trapezoid faces,” McInerney says. Parallelograms have two sets of parallel sides, but trapezoids only need to have one set of parallel sides. Introducing these more variable shapes makes this type of creasing more difficult to model, but potentially more versatile.

Breathing and shearing

“From our models and physical tests, we found that trapezoid faces have an entirely different class of responses,” McInerney shares. In other words — using trapezoids leads to new behavior.

The designs had the ability to change their shape in two distinct ways: "breathing" by expanding and contracting evenly, and “shearing" by deforming in a twisting motion. “We learned that we can use trapezoid faces in origami to constrain the system from bending in certain directions, which provides different functionality than parallelogram faces,” McInerney adds.

Surprisingly, the team also found that some of the behavior in parallelogram-based origami carried over to their trapezoidal origami, hinting at some features that might be universal across designs.

“While our research is theoretical, these insights could give us more opportunities for how we might deploy these structures and use them,” Rocklin shares.

Future folding

“We still have a lot of work to do,” McInerney says, sharing that there are two separate avenues of research to pursue. “The first is moving from trapezoids to more general quadrilateral faces, and trying to develop an effective model of the material behavior — similar to the way this study moved from parallelograms to trapezoids.” Those new models could help predict how creased materials might deform under different circumstances, and help researchers compare those results to sheets without any creases at all. “This will essentially let us assess the improvement our designs provide,” he explains.

“The second avenue is to start thinking deeply about how our designs might integrate into a real system,” McInerney continues. “That requires understanding where our models start to break down, whether it is due to the loading conditions or the fabrication process, as well as establishing effective manufacturing and testing protocols.”

“It’s a very challenging problem, but biology and nature are full of smart solids — including our own bodies — that deform in specific, useful ways when needed,” Rocklin says. “That’s what we’re trying to replicate with origami.”

This research was funded by the Office of Naval Research, European Union, Army Research Office, and National Science Foundation.

Mar. 21, 2025

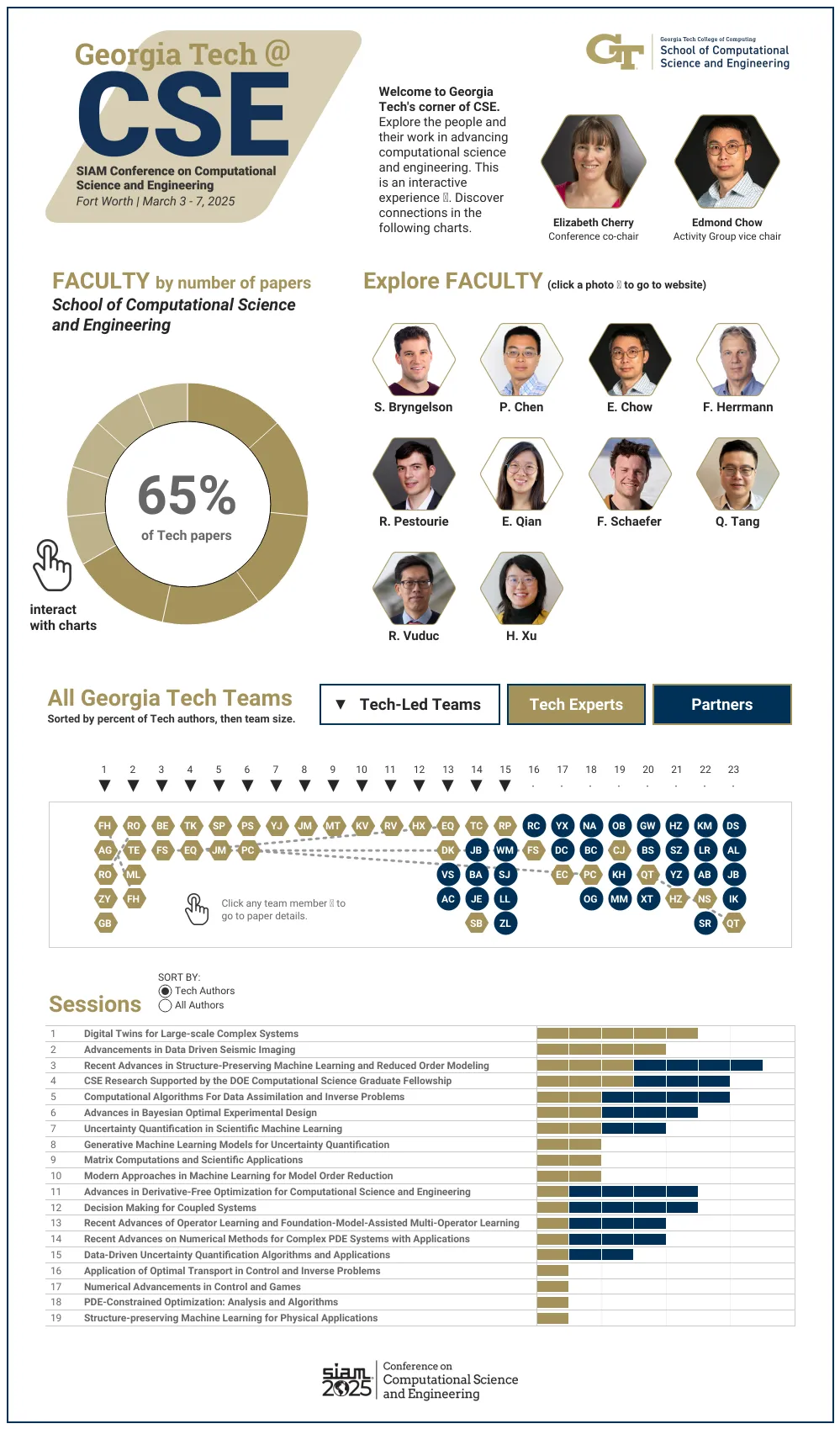

Many communities rely on insights from computer-based models and simulations. This week, a nest of Georgia Tech experts are swarming an international conference to present their latest advancements in these tools, which offer solutions to pressing challenges in science and engineering.

Students and faculty from the School of Computational Science and Engineering (CSE) are leading the Georgia Tech contingent at the SIAM Conference on Computational Science and Engineering (CSE25). The Society of Industrial and Applied Mathematics (SIAM) organizes CSE25, occurring March 3-7 in Fort Worth, Texas.

At CSE25, the School of CSE researchers are presenting papers that apply computing approaches to varying fields, including:

- Experiment designs to accelerate the discovery of material properties

- Machine learning approaches to model and predict weather forecasting and coastal flooding

- Virtual models that replicate subsurface geological formations used to store captured carbon dioxide

- Optimizing systems for imaging and optical chemistry

- Plasma physics during nuclear fusion reactions

[Related: GT CSE at SIAM CSE25 Interactive Graphic]

“In CSE, researchers from different disciplines work together to develop new computational methods that we could not have developed alone,” said School of CSE Professor Edmond Chow.

“These methods enable new science and engineering to be performed using computation.”

CSE is a discipline dedicated to advancing computational techniques to study and analyze scientific and engineering systems. CSE complements theory and experimentation as modes of scientific discovery.

Held every other year, CSE25 is the primary conference for the SIAM Activity Group on Computational Science and Engineering (SIAG CSE). School of CSE faculty serve in key roles in leading the group and preparing for the conference.

In December, SIAG CSE members elected Chow to a two-year term as the group’s vice chair. This election comes after Chow completed a term as the SIAG CSE program director.

School of CSE Associate Professor Elizabeth Cherry has co-chaired the CSE25 organizing committee since the last conference in 2023. Later that year, SIAM members reelected Cherry to a second, three-year term as a council member at large.

At Georgia Tech, Chow serves as the associate chair of the School of CSE. Cherry, who recently became the associate dean for graduate education of the College of Computing, continues as the director of CSE programs.

“With our strong emphasis on developing and applying computational tools and techniques to solve real-world problems, researchers in the School of CSE are well positioned to serve as leaders in computational science and engineering both within Georgia Tech and in the broader professional community,” Cherry said.

Georgia Tech’s School of CSE was first organized as a division in 2005, becoming one of the world’s first academic departments devoted to the discipline. The division reorganized as a school in 2010 after establishing the flagship CSE Ph.D. and M.S. programs, hiring nine faculty members, and attaining substantial research funding.

Ten School of CSE faculty members are presenting research at CSE25, representing one-third of the School’s faculty body. Of the 23 accepted papers written by Georgia Tech researchers, 15 originate from School of CSE authors.

The list of School of CSE researchers, paper titles, and abstracts includes:

Bayesian Optimal Design Accelerates Discovery of Material Properties from Bubble Dynamics

Postdoctoral Fellow Tianyi Chu, Joseph Beckett, Bachir Abeid, and Jonathan Estrada (University of Michigan), Assistant Professor Spencer Bryngelson

[Abstract]

Latent-EnSF: A Latent Ensemble Score Filter for High-Dimensional Data Assimilation with Sparse Observation Data

Ph.D. student Phillip Si, Assistant Professor Peng Chen

[Abstract]

A Goal-Oriented Quadratic Latent Dynamic Network Surrogate Model for Parameterized Systems

Yuhang Li, Stefan Henneking, Omar Ghattas (University of Texas at Austin), Assistant Professor Peng Chen

[Abstract]

Posterior Covariance Structures in Gaussian Processes

Yuanzhe Xi (Emory University), Difeng Cai (Southern Methodist University), Professor Edmond Chow

[Abstract]

Robust Digital Twin for Geological Carbon Storage

Professor Felix Herrmann, Ph.D. student Abhinav Gahlot, alumnus Rafael Orozco (Ph.D. CSE-CSE 2024), alumnus Ziyi (Francis) Yin (Ph.D. CSE-CSE 2024), and Ph.D. candidate Grant Bruer

[Abstract]

Industry-Scale Uncertainty-Aware Full Waveform Inference with Generative Models

Rafael Orozco, Ph.D. student Tuna Erdinc, alumnus Mathias Louboutin (Ph.D. CS-CSE 2020), and Professor Felix Herrmann

[Abstract]

Optimizing Coupled Systems: Insights from Co-Design Imaging and Optical Chemistry

Assistant Professor Raphaël Pestourie, Wenchao Ma and Steven Johnson (MIT), Lu Lu (Yale University), Zin Lin (Virginia Tech)

[Abstract]

Multifidelity Linear Regression for Scientific Machine Learning from Scarce Data

Assistant Professor Elizabeth Qian, Ph.D. student Dayoung Kang, Vignesh Sella, Anirban Chaudhuri and Anirban Chaudhuri (University of Texas at Austin)

[Abstract]

LyapInf: Data-Driven Estimation of Stability Guarantees for Nonlinear Dynamical Systems

Ph.D. candidate Tomoki Koike and Assistant Professor Elizabeth Qian

[Abstract]

The Information Geometric Regularization of the Euler Equation

Alumnus Ruijia Cao (B.S. CS 2024), Assistant Professor Florian Schäfer

[Abstract]

Maximum Likelihood Discretization of the Transport Equation

Ph.D. student Brook Eyob, Assistant Professor Florian Schäfer

[Abstract]

Intelligent Attractors for Singularly Perturbed Dynamical Systems

Daniel A. Serino (Los Alamos National Laboratory), Allen Alvarez Loya (University of Colorado Boulder), Joshua W. Burby, Ioannis G. Kevrekidis (Johns Hopkins University), Assistant Professor Qi Tang (Session Co-Organizer)

[Abstract]

Accurate Discretizations and Efficient AMG Solvers for Extremely Anisotropic Diffusion Via Hyperbolic Operators

Golo Wimmer, Ben Southworth, Xianzhu Tang (LANL), Assistant Professor Qi Tang

[Abstract]

Randomized Linear Algebra for Problems in Graph Analytics

Professor Rich Vuduc

[Abstract]

Improving Spgemm Performance Through Reordering and Cluster-Wise Computation

Assistant Professor Helen Xu

[Abstract]

News Contact

Bryant Wine, Communications Officer

bryant.wine@cc.gatech.edu

Mar. 06, 2025

Many communities rely on insights from computer-based models and simulations. This week, a nest of Georgia Tech experts are swarming an international conference to present their latest advancements in these tools, which offer solutions to pressing challenges in science and engineering.

Students and faculty from the School of Computational Science and Engineering (CSE) are leading the Georgia Tech contingent at the SIAM Conference on Computational Science and Engineering (CSE25). The Society of Industrial and Applied Mathematics (SIAM) organizes CSE25, occurring March 3-7 in Fort Worth, Texas.

At CSE25, the School of CSE researchers are presenting papers that apply computing approaches to varying fields, including:

- Experiment designs to accelerate the discovery of material properties

- Machine learning approaches to model and predict weather forecasting and coastal flooding

- Virtual models that replicate subsurface geological formations used to store captured carbon dioxide

- Optimizing systems for imaging and optical chemistry

- Plasma physics during nuclear fusion reactions

[Related: GT CSE at SIAM CSE25 Interactive Graphic]

“In CSE, researchers from different disciplines work together to develop new computational methods that we could not have developed alone,” said School of CSE Professor Edmond Chow.

“These methods enable new science and engineering to be performed using computation.”

CSE is a discipline dedicated to advancing computational techniques to study and analyze scientific and engineering systems. CSE complements theory and experimentation as modes of scientific discovery.

Held every other year, CSE25 is the primary conference for the SIAM Activity Group on Computational Science and Engineering (SIAG CSE). School of CSE faculty serve in key roles in leading the group and preparing for the conference.

In December, SIAG CSE members elected Chow to a two-year term as the group’s vice chair. This election comes after Chow completed a term as the SIAG CSE program director.

School of CSE Associate Professor Elizabeth Cherry has co-chaired the CSE25 organizing committee since the last conference in 2023. Later that year, SIAM members reelected Cherry to a second, three-year term as a council member at large.

At Georgia Tech, Chow serves as the associate chair of the School of CSE. Cherry, who recently became the associate dean for graduate education of the College of Computing, continues as the director of CSE programs.

“With our strong emphasis on developing and applying computational tools and techniques to solve real-world problems, researchers in the School of CSE are well positioned to serve as leaders in computational science and engineering both within Georgia Tech and in the broader professional community,” Cherry said.

Georgia Tech’s School of CSE was first organized as a division in 2005, becoming one of the world’s first academic departments devoted to the discipline. The division reorganized as a school in 2010 after establishing the flagship CSE Ph.D. and M.S. programs, hiring nine faculty members, and attaining substantial research funding.

Ten School of CSE faculty members are presenting research at CSE25, representing one-third of the School’s faculty body. Of the 23 accepted papers written by Georgia Tech researchers, 15 originate from School of CSE authors.

The list of School of CSE researchers, paper titles, and abstracts includes:

Bayesian Optimal Design Accelerates Discovery of Material Properties from Bubble Dynamics

Postdoctoral Fellow Tianyi Chu, Joseph Beckett, Bachir Abeid, and Jonathan Estrada (University of Michigan), Assistant Professor Spencer Bryngelson

[Abstract]

Latent-EnSF: A Latent Ensemble Score Filter for High-Dimensional Data Assimilation with Sparse Observation Data

Ph.D. student Phillip Si, Assistant Professor Peng Chen

[Abstract]

A Goal-Oriented Quadratic Latent Dynamic Network Surrogate Model for Parameterized Systems

Yuhang Li, Stefan Henneking, Omar Ghattas (University of Texas at Austin), Assistant Professor Peng Chen

[Abstract]

Posterior Covariance Structures in Gaussian Processes

Yuanzhe Xi (Emory University), Difeng Cai (Southern Methodist University), Professor Edmond Chow

[Abstract]

Robust Digital Twin for Geological Carbon Storage

Professor Felix Herrmann, Ph.D. student Abhinav Gahlot, alumnus Rafael Orozco (Ph.D. CSE-CSE 2024), alumnus Ziyi (Francis) Yin (Ph.D. CSE-CSE 2024), and Ph.D. candidate Grant Bruer

[Abstract]

Industry-Scale Uncertainty-Aware Full Waveform Inference with Generative Models

Rafael Orozco, Ph.D. student Tuna Erdinc, alumnus Mathias Louboutin (Ph.D. CS-CSE 2020), and Professor Felix Herrmann

[Abstract]

Optimizing Coupled Systems: Insights from Co-Design Imaging and Optical Chemistry

Assistant Professor Raphaël Pestourie, Wenchao Ma and Steven Johnson (MIT), Lu Lu (Yale University), Zin Lin (Virginia Tech)

[Abstract]

Multifidelity Linear Regression for Scientific Machine Learning from Scarce Data

Assistant Professor Elizabeth Qian, Ph.D. student Dayoung Kang, Vignesh Sella, Anirban Chaudhuri and Anirban Chaudhuri (University of Texas at Austin)

[Abstract]

LyapInf: Data-Driven Estimation of Stability Guarantees for Nonlinear Dynamical Systems

Ph.D. candidate Tomoki Koike and Assistant Professor Elizabeth Qian

[Abstract]

The Information Geometric Regularization of the Euler Equation

Alumnus Ruijia Cao (B.S. CS 2024), Assistant Professor Florian Schäfer

[Abstract]

Maximum Likelihood Discretization of the Transport Equation

Ph.D. student Brook Eyob, Assistant Professor Florian Schäfer

[Abstract]

Intelligent Attractors for Singularly Perturbed Dynamical Systems

Daniel A. Serino (Los Alamos National Laboratory), Allen Alvarez Loya (University of Colorado Boulder), Joshua W. Burby, Ioannis G. Kevrekidis (Johns Hopkins University), Assistant Professor Qi Tang (Session Co-Organizer)

[Abstract]

Accurate Discretizations and Efficient AMG Solvers for Extremely Anisotropic Diffusion Via Hyperbolic Operators

Golo Wimmer, Ben Southworth, Xianzhu Tang (LANL), Assistant Professor Qi Tang

[Abstract]

Randomized Linear Algebra for Problems in Graph Analytics

Professor Rich Vuduc

[Abstract]

Improving Spgemm Performance Through Reordering and Cluster-Wise Computation

Assistant Professor Helen Xu

[Abstract]

News Contact

Bryant Wine, Communications Officer

bryant.wine@cc.gatech.edu

Jan. 16, 2025

A researcher in Georgia Tech’s School of Interactive Computing has received the nation’s highest honor given to early career scientists and engineers.

Associate Professor Josiah Hester was one of 400 people awarded the Presidential Early Career Award for Scientists and Engineers (PECASE), the Biden Administration announced in a press release on Tuesday.

The PECASE winners’ research projects are funded by government organizations, including the National Science Foundation (NSF), the National Institutes of Health (NIH), the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and NASA. They will be invited to visit the White House later this year.

Hester joins Associate Professor Juan-Pablo Correa-Baena from the School of Materials Science and Engineering as the two Tech faculty who received the honor.

Hester said his nomination was based on the NSF Faculty Early Career Development Program (CAREER) award he received in 2022 as an assistant professor at Northwestern University. He said the NSF submits its nominations to the White House for the PECASE awards, but researchers are not informed until the list of winners is announced.

“For me, I always thought this was an unachievable, unassailable type of thing because of the reputation of the folks in computing who’ve won previously,” Hester said. “It was always a far-reaching goal. I was shocked. It’s something you would never in a million years think you would win.”

Hester is known for pioneering research in a new subfield of sustainable computing dedicated to creating battery-free devices powered by solar energy, kinetic energy, and radio waves. He co-led a team that developed the first battery-free handheld gaming device.

Last year, Hester co-authored an article published in the Association of Computing Machinery’s in-house journal, the Communications of the ACM, in which he coined the term “Internet of Battery-less Things.”

The Internet of Things is the network of physical computing devices capable of connecting to the internet and exchanging data. However, these devices eventually die. Landfills are overflowing with billions of them and their toxic power cells, harming our ecosystem.

In his CAREER award, Hester outlined projects that would work toward replacing the most used computing devices with sustainable, battery-free alternatives.

“I want everything to be an Internet of Batteryless Things — computational devices that could last forever,” Hester said. “I outlined a bunch of different ways that you could do that from the computer engineering side and a little bit from the human-computer interaction side. They all had a unifying theme of making computing more sustainable and climate-friendly.”

Hester is also a Sloan Research Fellow, an honor he received in 2022. In 2021, Popular Sciene named him to its Brilliant 10 list. He also received the Most Promising Engineer or Scientist Award from the American Indian Science Engineering Society, which recognizes significant contributions from the indigenous peoples of North America and the Pacific Islands in STEM disciplines.

President Bill Clinton established PECASE in 1996. The White House press release recognizes exceptional scientists and engineers who demonstrate leadership early in their careers and present innovative and far-reaching developments in science and technology.

News Contact

NATHAN DEEN

COMMUNICATIONS OFFICER

SCHOOL OF INTERACTIVE COMPUTING

Sep. 22, 2024

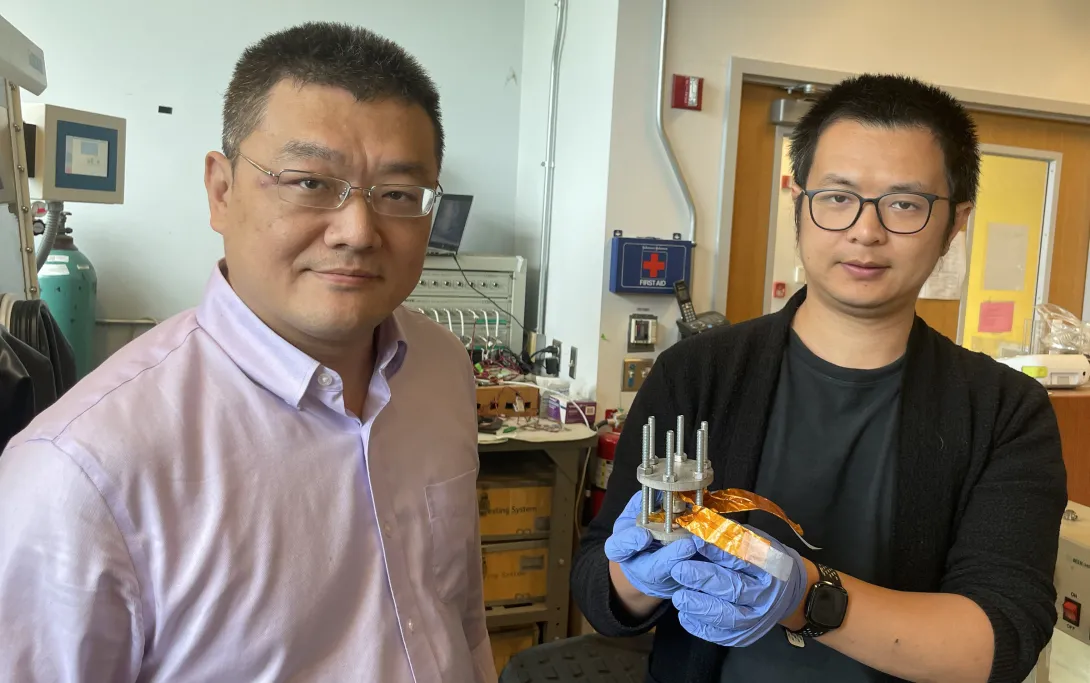

A multi-institutional research team led by Georgia Tech’s Hailong Chen has developed a new, low-cost cathode that could radically improve lithium-ion batteries (LIBs) — potentially transforming the electric vehicle (EV) market and large-scale energy storage systems.

“For a long time, people have been looking for a lower-cost, more sustainable alternative to existing cathode materials. I think we’ve got one,” said Chen, an associate professor with appointments in the George W. Woodruff School of Mechanical Engineering and the School of Materials Science and Engineering.

The revolutionary material, iron chloride (FeCl3), costs a mere 1-2% of typical cathode materials and canstore the same amount of electricity. Cathode materials affect capacity, energy, and efficiency, playing a major role in a battery’s performance, lifespan, and affordability.

“Our cathode can be a game-changer,” said Chen, whose team describes its work in Nature Sustainability. “It would greatly improve the EV market — and the whole lithium-ion battery market.”

First commercialized by Sony in the early 1990s, LIBs sparked an explosion in personal electronics, like smartphones and tablets. The technology eventually advanced to fuel electric vehicles, providing a reliable, rechargeable, high-density energy source. But unlike personal electronics, large-scale energy users like EVs are especially sensitive to the cost of LIBs.

Batteries are currently responsible for about 50% of an EV’s total cost, which makes these clean-energy cars more expensive than their internal combustion, greenhouse-gas-spewing cousins. The Chen team’s invention could change that.

Building a Better Battery

Compared to old-fashioned alkaline and lead-acid batteries, LIBs store more energy in a smaller package and power a device longer between charges. But LIBs contain expensive metals, including semiprecious elements like cobalt and nickel, and they have a high manufacturing cost.

So far, only four types of cathodes have been successfully commercialized for LIBs. Chen’s would be the fifth, and it would represent a big step forward in battery technology: the development of an all-solid-state LIB.

Conventional LIBs use liquid electrolytes to transport lithium ions for storing and releasing energy. They have hard limits on how much energy can be stored, and they can leak and catch fire. But all-solid-state LIBs use solid electrolytes, dramatically boosting a battery’s efficiency and reliability and making it safer and capable of holding more energy. These batteries, still in the development and testing phase, would be a considerable improvement.

As researchers and manufacturers across the planet race to make all-solid-state technology practical, Chen and his collaborators have developed an affordable and sustainable solution. With the FeCl3 cathode, a solid electrolyte, and a lithium metal anode, the cost of their whole battery system is 30-40% of current LIBs.

“This could not only make EVs much cheaper than internal combustion cars, but it provides a new and promising form of large-scale energy storage, enhancing the resilience of the electrical grid,” Chen said. “In addition, our cathode would greatly improve the sustainability and supply chain stability of the EV market.”

Solid Start to New Discovery

Chen’s interest in FeCl3 as a cathode material originated with his lab’s research into solid electrolyte materials. Starting in 2019, his lab tried to make solid-state batteries using chloride-based solid electrolyteswith traditional commercial oxide-based cathodes. It didn’t go well — the cathode and electrolyte materials didn’t get along.

The researchers thought a chloride-based cathode could provide a better pairing with the chloride electrolyte to offer better battery performance.

“We found a candidate (FeCl3) worth trying, as its crystal structure is potentially suitable for storing and transporting Li ions, and fortunately, it functioned as we expected,” said Chen.

Currently, the most popularly used cathodes in EVs are oxides and require a gigantic amount of costly nickel and cobalt, heavy elements that can be toxic and pose an environmental challenge. In contrast, the Chen team’s cathode contains only iron (Fe) and chlorine (Cl)—abundant, affordable, widely used elements found in steel and table salt.

In their initial tests, FeCl3 was found to perform as well as or better than the other, much more expensive cathodes. For example, it has a higher operational voltage than the popularly used cathode LiFePO4 (lithium iron phosphate, or LFP), which is the electrical force a battery provides when connected to a device, similar to water pressure from a garden hose.

This technology may be less than five years from commercial viability in EVs. For now, the team will continue investigating FeCl3 and related materials, according to Chen. The work was led by Chen and postdoc Zhantao Liu (the lead author of the study). Collaborators included researchers from Georgia Tech’s Woodruff School (Ting Zhu) and the School of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences (Yuanzhi Tang), as well as the Oak Ridge National Laboratory (Jue Liu) and the University of Houston (Shuo Chen).

“We want to make the materials as perfect as possible in the lab and understand the underlying functioning mechanisms,” Chen said. “But we are open to opportunities to scale up the technology and push it toward commercial applications.”

CITATION: Zhantao Liu, Jue Liu, Simin Zhao, Sangni Xun, Paul Byaruhanga, Shuo Chen, Yuanzhi Tang, Ting Zhu, Hailong Chen. “Low-cost iron trichloride cathode for all-solid-state lithium-ion batteries.” Nature Sustainability.

FUNDING: National Science Foundation (Grant Nos. 1706723 and 2108688)

News Contact

Sep. 03, 2024

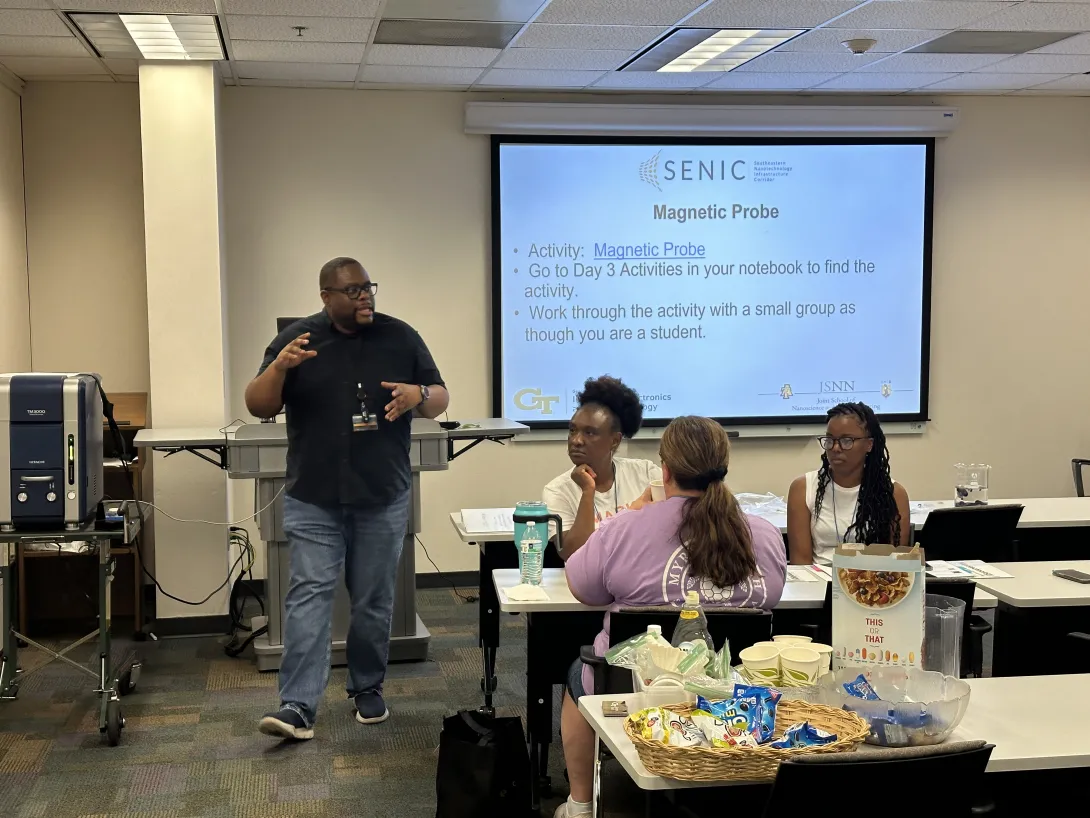

The Institute for Matter and Systems (IMS) has received $700,000 in funding from the National Science Foundation (NSF) for two education and outreach programs.

The awards will support the Research Experience for Undergraduates (REU) and Research Experience for Teachers (RET) programs at Georgia Tech. The REU summer internship program provides undergraduate students from two- and four-year programs the chance to perform cutting-edge research at the forefront of nanoscale science and engineering. The RET program for high school teachers and technical college faculty offers a paid opportunity to experience the excitement of nanotechnology research and to share this experience in their classrooms.

“This NSF funding allows us to be able to do more with the programs,” said Mikkel Thomas, associate director for education and outreach. “These are programs that have existed in the past, but we haven’t had external funding for the last three years. The NSF support allows us to do more — bring more students into the program or increase the RET stipends.”

In addition to the REU and RET programs, IMS offers short courses and workshops focused on professional development, instructional labs for undergraduate and graduate students, a certificate for veterans in microelectronics and nano-manufacturing, and community engagement activities such as the Atlanta Science Festival.

News Contact

Amelia Neumeister | Communications Program Manager

Aug. 30, 2024

The Cloud Hub, a key initiative of the Institute for Data Engineering and Science (IDEaS) at Georgia Tech, recently concluded a successful Call for Proposals focused on advancing the field of Generative Artificial Intelligence (GenAI). This initiative, made possible by a generous gift funding from Microsoft, aims to push the boundaries of GenAI research by supporting projects that explore both foundational aspects and innovative applications of this cutting-edge technology.

Call for Proposals: A Gateway to Innovation

Launched in early 2024, the Call for Proposals invited researchers from across Georgia Tech to submit their innovative ideas on GenAI. The scope was broad, encouraging proposals that spanned foundational research, system advancements, and novel applications in various disciplines, including arts, sciences, business, and engineering. A special emphasis was placed on projects that addressed responsible and ethical AI use.

The response from the Georgia Tech research community was overwhelming, with 76 proposals submitted by teams eager to explore this transformative technology. After a rigorous selection process, eight projects were selected for support. Each awarded team will also benefit from access to Microsoft’s Azure cloud resources..

Recognizing Microsoft’s Generous Contribution

This successful initiative was made possible through the generous support of Microsoft, whose contribution of research resources has empowered Georgia Tech researchers to explore new frontiers in GenAI. By providing access to Azure’s advanced tools and services, Microsoft has played a pivotal role in accelerating GenAI research at Georgia Tech, enabling researchers to tackle some of the most pressing challenges and opportunities in this rapidly evolving field.

Looking Ahead: Pioneering the Future of GenAI

The awarded projects, set to commence in Fall 2024, represent a diverse array of research directions, from improving the capabilities of large language models to innovative applications in data management and interdisciplinary collaborations. These projects are expected to make significant contributions to the body of knowledge in GenAI and are poised to have a lasting impact on the industry and beyond.

IDEaS and the Cloud Hub are committed to supporting these teams as they embark on their research journeys. The outcomes of these projects will be shared through publications and highlighted on the Cloud Hub web portal, ensuring visibility for the groundbreaking work enabled by this initiative.

Congratulations to the Fall 2024 Winners

- Annalisa Bracco | EAS "Modeling the Dispersal and Connectivity of Marine Larvae with GenAI Agents" [proposal co-funded with support from the Brook Byers Institute for Sustainable Systems]

- Yunan Luo | CSE “Designing New and Diverse Proteins with Generative AI”

- Kartik Goyal | IC “Generative AI for Greco-Roman Architectural Reconstruction: From Partial Unstructured Archaeological Descriptions to Structured Architectural Plans”

- Victor Fung | CSE “Intelligent LLM Agents for Materials Design and Automated Experimentation”

- Noura Howell | LMC “Applying Generative AI for STEM Education: Supporting AI literacy and community engagement with marginalized youth”

- Neha Kumar | IC “Towards Responsible Integration of Generative AI in Creative Game Development”

- Maureen Linden | Design “Best Practices in Generative AI Used in the Creation of Accessible Alternative Formats for People with Disabilities”

- Surya Kalidindi | ME & MSE “Accelerating Materials Development Through Generative AI Based Dimensionality Expansion Techniques”

- Tuo Zhao | ISyE “Adaptive and Robust Alignment of LLMs with Complex Rewards”

News Contact

Christa M. Ernst - Research Communications Program Manager

christa.ernst@research.gatech.edu

Aug. 19, 2024

Nylon, Teflon, Kevlar. These are just a few familiar polymers — large-molecule chemical compounds — that have changed the world. From Teflon-coated frying pans to 3D printing, polymers are vital to creating the systems that make the world function better.

Finding the next groundbreaking polymer is always a challenge, but now Georgia Tech researchers are using artificial intelligence (AI) to shape and transform the future of the field. Rampi Ramprasad’s group develops and adapts AI algorithms to accelerate materials discovery.

This summer, two papers published in the Nature family of journals highlight the significant advancements and success stories emerging from years of AI-driven polymer informatics research. The first, featured in Nature Reviews Materials, showcases recent breakthroughs in polymer design across critical and contemporary application domains: energy storage, filtration technologies, and recyclable plastics. The second, published in Nature Communications, focuses on the use of AI algorithms to discover a subclass of polymers for electrostatic energy storage, with the designed materials undergoing successful laboratory synthesis and testing.

“In the early days of AI in materials science, propelled by the White House’s Materials Genome Initiative over a decade ago, research in this field was largely curiosity-driven,” said Ramprasad, a professor in the School of Materials Science and Engineering. “Only in recent years have we begun to see tangible, real-world success stories in AI-driven accelerated polymer discovery. These successes are now inspiring significant transformations in the industrial materials R&D landscape. That’s what makes this review so significant and timely.”

AI Opportunities

Ramprasad’s team has developed groundbreaking algorithms that can instantly predict polymer properties and formulations before they are physically created. The process begins by defining application-specific target property or performance criteria. Machine learning (ML) models train on existing material-property data to predict these desired outcomes. Additionally, the team can generate new polymers, whose properties are forecasted with ML models. The top candidates that meet the target property criteria are then selected for real-world validation through laboratory synthesis and testing. The results from these new experiments are integrated with the original data, further refining the predictive models in a continuous, iterative process.

While AI can accelerate the discovery of new polymers, it also presents unique challenges. The accuracy of AI predictions depends on the availability of rich, diverse, extensive initial data sets, making quality data paramount. Additionally, designing algorithms capable of generating chemically realistic and synthesizable polymers is a complex task.

The real challenge begins after the algorithms make their predictions: proving that the designed materials can be made in the lab and function as expected and then demonstrating their scalability beyond the lab for real-world use. Ramprasad’s group designs these materials, while their fabrication, processing, and testing are carried out by collaborators at various institutions, including Georgia Tech. Professor Ryan Lively from the School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering frequently collaborates with Ramprasad’s group and is a co-author of the paper published in Nature Reviews Materials.

"In our day-to-day research, we extensively use the machine learning models Rampi’s team has developed,” Lively said. “These tools accelerate our work and allow us to rapidly explore new ideas. This embodies the promise of ML and AI because we can make model-guided decisions before we commit time and resources to explore the concepts in the laboratory."

Using AI, Ramprasad’s team and their collaborators have made significant advancements in diverse fields, including energy storage, filtration technologies, additive manufacturing, and recyclable materials.

Polymer Progress

One notable success, described in the Nature Communications paper, involves the design of new polymers for capacitors, which store electrostatic energy. These devices are vital components in electric and hybrid vehicles, among other applications. Ramprasad’s group worked with researchers from the University of Connecticut.

Current capacitor polymers offer either high energy density or thermal stability, but not both. By leveraging AI tools, the researchers determined that insulating materials made from polynorbornene and polyimide polymers can simultaneously achieve high energy density and high thermal stability. The polymers can be further enhanced to function in demanding environments, such as aerospace applications, while maintaining environmental sustainability.

“The new class of polymers with high energy density and high thermal stability is one of the most concrete examples of how AI can guide materials discovery,” said Ramprasad. “It is also the result of years of multidisciplinary collaborative work with Greg Sotzing and Yang Cao at the University of Connecticut and sustained sponsorship by the Office of Naval Research.”

Industry Potential

The potential for real-world translation of AI-assisted materials development is underscored by industry participation in the Nature Reviews Materials article. Co-authors of this paper also include scientists from Toyota Research Institute and General Electric. To further accelerate the adoption of AI-driven materials development in industry, Ramprasad co-founded Matmerize Inc., a software startup company recently spun out of Georgia Tech. Their cloud-based polymer informatics software is already being used by companies across various sectors, including energy, electronics, consumer products, chemical processing, and sustainable materials.

“Matmerize has transformed our research into a robust, versatile, and industry-ready solution, enabling users to design materials virtually with enhanced efficiency and reduced cost,” Ramprasad said. “What began as a curiosity has gained significant momentum, and we are entering an exciting new era of materials by design.”

News Contact

Tess Malone, Senior Research Writer/Editor

tess.malone@gatech.edu

Pagination

- 1 Page 1

- Next page