Jul. 14, 2020

Dr. Christine Ries has been invited to serve on a Review Panel for the New NSF Future Manufacturing Program on Eco-Manufacturing.

This new multidisciplinary NSF program supports fundamental research and education of a future workforce that would enable the types of manufacturing that are not existent yet or are at such early stages of development they are not yet viable (Future Manufacturing). Reviews considered impacts on the economy, workforce, human behavior, and society at large.

News Contact

Professor Christine Ries

christine.ries@econ.gatech.edu

Jul. 01, 2020

Jun. 30, 2020

As America’s leading research universities ramp up laboratory operations that were shut down by Covid-19 in March, they’re encountering a perfect storm of challenges in providing personal protective equipment (PPE) – surgical masks, cloth face coverings, gloves, hand sanitizer, and disinfectant materials.

Global PPE supply chains have been severely disrupted by the coronavirus pandemic, producing long lead times and unreliable deliveries. At the same time, Covid-19 precautions are mandating the use of PPE in laboratories where it wasn’t required before, such as computer and electronics labs. And as researchers, staff, and graduate students slowly come back to the lab, predicting how many people will be at work on any given day creates yet another unknown.

At the Georgia Institute of Technology, supply chain and logistics experts have put their knowledge to work on the problem, using the kind of modeling and machine learning technologies that major retailers rely on to keep products on store shelves. In just one month, the research team has built an automated centralized system to replace traditional purchasing systems in which individual labs had to hunt for their own supplies.

By asking researchers to report details of the PPE they use each day, the labs will provide data the system needs to predict demand, allowing Georgia Tech to place large orders and stock a centralized warehouse that will help bridge the gap between supply chain hiccups. Based on usage data, the system will know when each lab’s stock of PPE needs to be resupplied from distribution centers located in 22 major laboratory buildings. The goal will be for each lab to have a robust three-day supply of PPE at all times.

“We need to make sure that every researcher, staff member, and graduate student is going to be protected properly,” said Benoit Montreuil, a professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Industrial and Systems Engineering (ISYE) and director of the Georgia Tech Supply Chain and Logistics Institute. “We are dealing with a very volatile situation for supply capacity, lead times, alternate sources, and reliability. With this system, we can ensure that the distribution of PPE throughout campus will be done in an efficient, seamless, responsive, and fair way.”

With $1 billion in sponsored activity during 2019, Georgia Tech has hundreds of research laboratories studying everything from viral antibodies and stem cells to robotics and electronic defense. In peak times, those researchers are expected to use 400,000 gloves a month and 20,000 surgical masks. With new sanitizing guidelines, they’re expected to use more than 4,000 gallons of hand sanitizer a month – but nobody really knows for sure, because this wasn’t widely required before.

Prior to the Covid-19 pandemic, most labs were responsible for purchasing their own PPE. But with so many labs worldwide now hunting for materials in the same disrupted supply chains, that’s no longer possible.

“Georgia Tech can ensure better success in obtaining PPE by buying in very large quantities instead of asking individual lab managers to try to find stock on their own,” said Robert Butera, Georgia Tech’s Vice President for Research Development and Operations. “We can track down the best suppliers and create a buffer in the system. We’ll also be able to identify who are the most reliable suppliers.”

From individual laboratories, the system needs daily reports of how many gloves, masks, and other PPE are used. The system aggregates the numbers and uses that information to predict future usage, allowing Montreuil and his team to provide information to Georgia Tech’s Environmental Health and Safety (EHS). Baseline information obtained during Phase 1 of the research ramp-up will help plan for PPE needs as the number of researchers increases during Phase 2.

Individual labs won’t need to place orders unless than they encounter an unexpected change in demand.

“Rather than principal investigators requesting PPE for their labs and having to anticipate demand, they will log usage and the platform will do all the back-end work to make sure there’s a three-day supply in each lab and a two-week supply in the buildings,” Butera explained. “We are switching from making requests to logging usage in real time. People have to log their use of PPE on daily basis to make sure they are supplied.”

The new system will supply an estimated 95% of PPE needed on campus. Other items that are purchased less frequently, such as lab coats and shoe coverings, will continue to be ordered through traditional means. Those other supplies may be added to the system later.

“The idea is to focus right now on the key PPEs that are most critical from a supply perspective,” said Montreuil. “We will be revising consumption predictions on a daily basis and transferring this information into an overall demand forecast for PPEs.”

Georgia Tech’s research enterprise is ramping up in two phases over the summer. The first phase began June 18, and the second will start July 13. The new PPE supply system launches July 1.

To initiate the system, EHS has provided a stock of supplies to each lab, and that initial stock will be replenished based on the new system. In Phase 2 of the research ramp-up, the system will grow to include distribution centers in more than 50 campus buildings. At this point, Georgia Tech Research Institute (GTRI) labs will receive their PPE through a separate supply system.

PPE distribution will begin at a campus warehouse managed by EHS. To meet the predicted demand, the warehouse will regularly distribute supplies to buildings, where managers will in turn supply individual labs. How labs receive their supplies will depend on building-level plans developed by managers, Butera said.

The centralized and automated system will for the first time allow administrators to know how much stock of each PPE item is available on campus. Ensuring adequate stock has become increasingly important with the protection needs of the Covid-19 environment.

While researchers who work with biological and chemical materials are accustomed to using and maintaining PPE stocks, keeping up with face masks and disinfectant stocks will be a new practice for others.

“In my lab in ISYE, nobody was using PPE before Covid-19 because we are only around workstations and computer displays,” said Montreuil. “Now, ISYE researchers won’t be able to get into the lab unless they have masks and we will provide hand sanitizer. We will have to get used to this change.”

Georgia Tech has one of the world’s best industrial engineering schools, and supply chain and logistics research is a key part of that. But even that expertise is challenged by the global logistics issues created by the pandemic, he added.

“The basics of inventory replenishment systems are well known,” Montreuil said. “But most of the time, the assumptions made in the models are very different from the environment we have now. With highly disrupted settings around the world, we find ourselves on a new frontier. It’s not a lab problem, a building problem, or a Georgia Tech problem. It’s a global challenge, and it affects everybody.”

Below are some frequently-asked questions about PPE supplies.

Where is the form to log use of PPE?

The form is available at this link.

Which PPE items are covered by the system?

Consumption of the following items should be reported: Pairs of nitrile gloves by size (S/M/L/XL), pairs of latex gloves by size (M/L), pairs of vinyl gloves, individual surgical masks, individual cloth masks, hand sanitizer by bottle, disinfecting spray by bottle, and disinfecting wipes by package.

How should consumption be reported?

Reporting usage by individual lab occupant would be most useful to the system because it will provide the most detailed data for predicting future use. But if labs cannot report usage by individuals working in the lab, they should provide daily data on the entire lab.

When are labs expected to begin reporting their daily consumption of PPE?

The system is operational now, and labs will be expected to start using it July 1.

Will GTRI labs obtain their PPE through this system?

No, GTRI has a separate system for providing PPE.

How will PPE supplies be restocked from buildings to individual laboratories?

Building managers will receive supplies from EHS and will be responsible for determining how labs will receive replenishment.

What should labs do with empty hand sanitizer and disinfectant spray bottles?

Empty hand sanitizer and disinfectant spray bottles should be returned to building managers for refill from bulk supplies. There is a shortage of bottles and reuse will help prevent shortages.

What is the lead time for PPE materials ordered from suppliers?

That varies according to the item. The median lead time for nitrile gloves has ranged from 11 to 53 days depending on glove size, with shortest for various sizes ranging between 7 and 11 days while the longest ranged between 11 and 130 days, depicting a high volatility. Supply chain challenges for hand sanitizer led Georgia Tech to work with non-traditional suppliers to create an alternative supply chain based on ethanol rather than isopropyl alcohol.

If labs will be provided with a robust three-day stock, how much will be at building depots?

Buildings should have a robust two-week supply of critical PPE items. The adjective robust is important as the aim is not to keep a stock covering an average three-day demand in labs, and an average two-week demand in buildings, but rather enough to cover demand considering consumption and supply stochasticity with degree of confidence. The three-day and two-weeks targets will be dynamically adjusted according to learning of the overall demand and supply chain dynamics.

Where can I get more information about accessing the consumption reporting system?

Please visit https://ehs.gatech.edu/covid-19/isye.

What if labs need certain supplies immediately?

An urgent request can be made using the urgent request form. At this point, ISYE is monitoring the requests and will notify the building manager. In the near future, requests will go directly to the building manager (or other point of contact).

Research News

Georgia Institute of Technology

177 North Avenue

Atlanta, Georgia 30332-0181 USA

Media Relations Contact: John Toon (404-894-6986) (jtoon@gatech.edu)

Writer: John Toon

News Contact

John Toon

Research News

(404) 894-6986

Jun. 16, 2020

So many people Seth Marder spoke to didn’t see the hand sanitizer crisis brewing. The country was going to run dangerously short if someone did not act urgently.

The professor at the Georgia Institute of Technology rallied colleagues and partners around the cause in March, and by early June, they had replaced a key component of hand sanitizer, created a new supply chain, and initiated their own donation of 7,000 gallons of a newly designed sanitizer to medical facilities.

Its name: Han-I-Size White & Gold, named for the colors of Georgia Tech. The new supply chain also may ensure that hand sanitizer producers across the country do not run out of the main active ingredient, alcohol, but the team’s path to success was a stony labyrinth.

“This project was on life support so many times because people did not understand how severe this shortage was going to be,” said Marder, a Regents Professor in Georgia Tech’s School of Chemistry and Biochemistry. “I called hospitals and institutions to assess the need and heard the same thing over and over: ‘No, we just got a delivery. We have no need. You’re wasting your time.’”

Marder was not. Contacts at major chemical suppliers of hand sanitizer ingredients said that a critical shortage of alcohol, particularly the one usually in hand sanitizer, isopropanol, was coming.

“Isopropanol plants in the U.S. were running at full capacity and still didn’t have enough. People were using pharmaceutical-grade ethanol now, too, but it was also in short supply. We weren’t going to have enough of either; I mean the whole United States was running low,” Marder said.

Clean hands cabal

Marder hastily drafted Chris Luettgen, a professor of practice in Georgia Tech’s School of Chemical and Biomolecular Engineering, George White, interim vice president of Georgia Tech’s Office of Industry Collaboration, and Atif Dabdoub, a Georgia Tech alumnus and owner of a local chemical company, Unichem Technologies, Inc.

To the three chemists and the business professional, it seemed simple: Mix alcohol with water, peroxide, and the moisturizer glycerin then bottle and ship it. That bubble burst quickly.

Luettgen, who had worked in the consumer products industry for 25 years at Kimberly-Clark Corporation and knew how to take products to market, had to plow through constant unexpected supply chain barriers and bureaucracy while White forged connections between companies. Neither the supply chain nor the business relationships had existed before, and the teams’ phones stayed glued to their ears night and day as they created them from scratch.

“When I worked for Kimberly-Clark, getting a new product out would take the company nine to 18 months, and the three of us had to get this done in weeks. The demand was there, and people were getting sick in some cases from lack of sanitizing. We felt speed was necessary to meet the growing demand. Seth told me to push this across the goal line, and I put everything into it,” Luettgen said.

“Georgia Tech is about the power to convene. Companies and stakeholders are eager to come to the table here to make things happen,” White said about forging new business ties. “Not everyone has that incredible recognition as a problem solver with the brainpower amassed here.”

Stinking of gin

Purchasing truckloads of alcohol was priority one.

Boutique liquor distilleries in Georgia were already converting to sanitizer ethyl alcohol production, but output was nowhere near enough to meet demand. ExxonMobil connected the team with Eco-Energy, a company that handles fuel-grade ethanol as a gasoline additive.

“The amount of ethanol that’s made for fuel in the U.S. is 1,500 times the amount of the isopropanol made. They could drain off about 1 percent of what is used for fuel and double or triple the amount of alcohol available for hand sanitizer in this country. And the fuel companies wouldn’t even notice it was gone, especially since hardly anyone was driving anymore,” Marder said.

But then prospective hand sanitizer distributors crimped their noses at that ethanol, saying it smelled odd.

“I thought, ‘This has the makings of a screenplay.’ I asked the distributor if we could come over to smell a sample for ourselves,” White said. “It needed a little love.”

Eco-Fuels produced the highly refined ethanol and then processed it through carbon filtration to increase purity and reduce odor. Atlanta-based chemical manufacturer, Momar, Inc., oversaw production, packaging, and distribution of Han-I-Size White & Gold.

The Georgia Tech team garnered funding through a donation from insurer Aflac Incorporated allocated through the Global Center for Medical Innovation (GCMI), a Georgia Tech affiliated non-profit organization that guides new experimental medical solutions to market. Aflac’s gift of $2 million through GCMI has also expedited the development, production, and purchase of other PPE to donate to health care workers.

In addition, GCMI helped guide the hand sanitizer through regulatory processes and to market. In a another development, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration was also aware of the dire shortage of alcohol for sanitizer and issued waivers for the pandemic to allow for use of ethanol in sanitizers without having to meet usual specifications.

Water, water everywhere

Arkema, Inc. donated hydrogen peroxide, which was delivered to PSG Functional Materials, which mixed and packaged the product then shipped with no delivery fee to Atlanta. Though water is ubiquitous, hand sanitizer requires purified water, and the Coca-Cola Company donated a tanker truck of it just when White was pondering desperate measures.

“If I have to get a truck to go pick up water and drive it, I’ll do it myself,” he said.

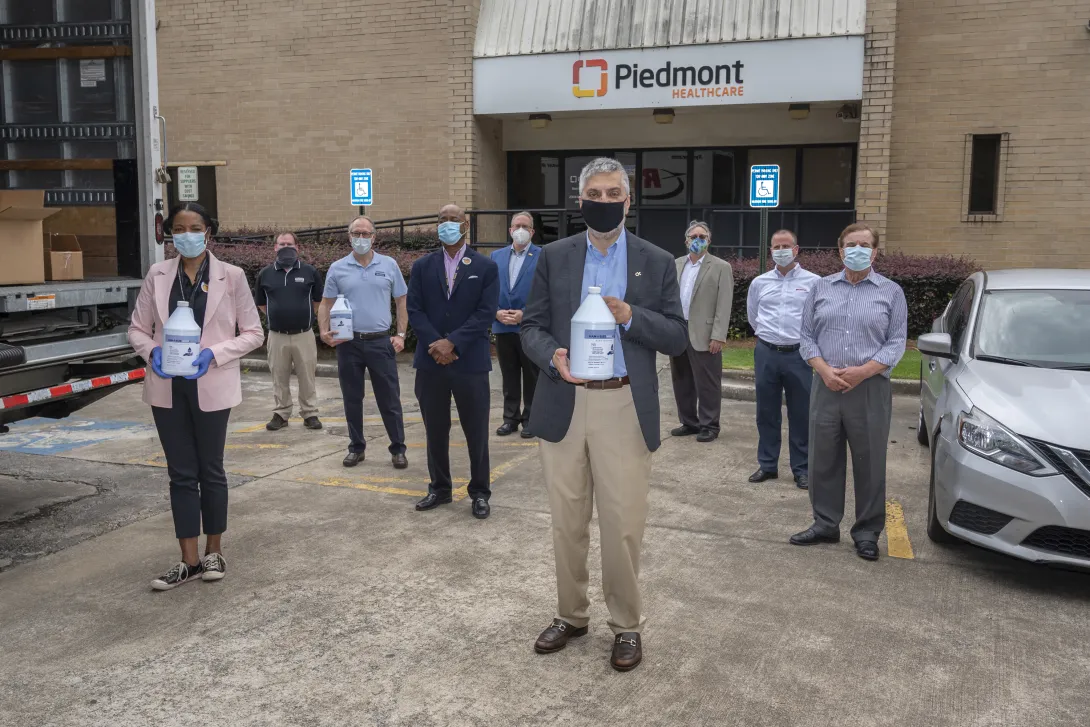

Finally, the first few hundred gallons of donated Han-I-Size White & Gold rolled into Piedmont Healthcare in Atlanta and Brightmoor Nursing Center in Griffin, Georgia, in the second week of June 2020.

GCMI is facilitating donations of the 7,000 gallons nationwide. Separate from the Aflac-financed donations, Momar will continue to manufacture the new hand sanitizing formula commercially to include in its regular product lineup, and Georgia Tech will be able to purchase it at a reduced rate to help protect researchers now returning to their labs.

The new supply chain, the first of its kind, of “waiver-grade” ethanol has given hand sanitizer producers across the country a new opportunity to re-supply America.

“Hopefully, we helped solved a national need,” Luettgen said.

Read about what else we are doing to help in the Covid-19 crisis.

Here's how to subscribe to our free science and technology email newsletter

Writer & media inquiries: Ben Brumfield, ben.brumfield@comm.gatech.edu or John Toon (404-894-6986), jtoon@gatech.edu.

Georgia Institute of Technology

Jun. 15, 2020

Dipayan Banerjee, a rising second-year Ph.D. student studying operations research in the H. Milton Stewart School of Industrial and Systems Engineering, has been awarded a Graduate Research Fellowship (GRF) by the National Science Foundation (NSF). Banerjee, who has a bachelor’s degree in industrial engineering and management sciences from Northwestern University, is co-advised by UPS Professor of Logistics Alan Erera and Leo and Louise Benatar Early Career Professor and Associate Professor Alejandro Toriello.

“Dipayan is a rising researcher in logistics, and the NSF fellowship is yet another accolade testifying to his promising young career,” said Toriello. “I look forward to working with him in the coming years in last-mile logistics and e-commerce, an exciting area where Dipayan has the potential to make a significant contribution.”

Banerjee is studying the tactical design of last-mile delivery systems, which are a challenging supply chain problem. The last mile in a supply chain represents the transport of goods being delivered, for example, from a local warehouse to a home or business. Specifically, Banerjee is looking at issues related to designing delivery fleets and vehicle dispatch policies for cost-effective last-mile delivery within a particular region.

“You can pack a big truck full of bulk quantities of goods and efficiently transport them across the U.S.,” Banerjee explained. “But getting the goods to a consumer’s home is less efficient, since individual items are being delivered. You could also see the importance of last-mile logistics during the Covid-19 lockdowns, when so many people were ordering and receiving their groceries at home.”

Beyond the demand dictated by the pandemic, Banerjee noted that e-commerce supply chains have become fundamental to the average person’s life, and hundreds of companies ranging from bakeries to florists are responding accordingly.

“It’s a really exciting time to be studying transportation and logistics systems,” he says. “There are many fascinating new challenges being faced in the last mile as companies seek to deliver more and more goods on increasingly tighter deadlines. These include issue of accessibility and environmental sustainability. We also have so much data and advanced computing power at our disposal that wasn’t available five or 10 years ago. I’m excited about the opportunity to develop new operations research approaches to solving these problems.”

Established in 1951, the NSF Graduate Research Fellowship is the oldest fellowship of its kind. The fellowship recognizes and supports outstanding graduate students in STEM disciplines who are pursuing research-based graduate degrees at accredited U.S. institutions. Fellows receive a three-year annual stipend of $34,000, along with a $12,000 cost of education allowance for tuition and fees (paid to the institution), opportunities for international research and professional development, and the freedom to conduct their own research at any accredited U.S. institution of graduate education they choose.

May. 28, 2020

IDEaS recently awarded a series of grants to stimulate the research efforts of Georgia Tech’s brightest minds in data science and related disciplines. Faculty and student research programs targeted for IDEaS awards must demonstrate research goals that will be highly cross-disciplinary and emphasize how data science can assist in related research areas.

The Data Science Research Scholarships program will support scholarships for the Spring 2020 semester and focus on Ph.D. student research that enables new collaborative research or adds a data science dimension to established research projects. Each scholarship will fund 50% of the cost of a GRA appointment, with the project PI funding the remaining 50%.

Data Science Research Scholarships 2020 Awards

- JC Gumbart (Physics) & David Sherrill (Chemistry): Force-field Development to Enable Simulations of Xeno-nucleic Acids

- Xiuwei Zhang (CSE) & Haesun Park (CSE): Development of an Integrative Clustering Method for Single Cells

- Vince Calhoun (ECE) & Audrey Duarte (Psych): The Chronnectomics of Memory

- Annalisa Bracco (EAS), Jie He (EAS) & Matt J. Kusner (University College London): Machine-learning Techniques for Cloud Modeling

- Toyya Pujol-Mitchell (ISYE), Nicoleta Serban (ISyE) & Constantine Dovrolis (CS): Network Weight Prediction Using Node Attributes

- Xiaofan Liang (City & Reg Planning), Clio Andris (City & Reg Planning) & Diyi Yang (IC): Advancing Metrics for Spatial Social Networks in the Era of Big Data

- Omar Asensio (Public Policy): Do Micromobility Options Reduce Traffic Congestion? Quasi-experimental Evidence from Uber Movement Data

- Constantine Dovrolis (CS) & Kelly F. Ethun (Emory/Yerkes): Connections Between Social Behavior and Food Intake in Rhesus Macaques

- Diyi Yang (IC) & Mai ElSherief (IC): Defining, Characterizing, and Detecting Implicit Discriminatory Speech Online

- Umakishore Ramachandran (CS) & Zhuangdi Xu (CS): Generating Labeled Vehicle Tracking Dataset for Large-scale Geo-Distributed Camera Networks

- Surya R. Kalidindi (ME/CSE/MSE) & Christopher Saldana (ME): Advanced Materials-Manufacturing Data Curation

- Agata Rozga (IC), Thomas Ploetz (IC) & external: Annotation of Datasets from Severe Behavior Treatment Program at the Marcus Autism Center

Data Science Partnership 2020 Awards

- Diyi Yang (IC): Allen Institute for AI and University of Washington

- Josh Kacher (MSE): Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory

- Rachel Cummings (ISyE): Georgetown University and U.S. Census Bureau

Data Science Speaker Travel Awards supports visits to the Georgia Tech campus by external experts in the areas of data science foundations or data-driven discovery in any discipline. Funds may be used to host a guest speaker for the IDEaS seminar series, or to participate in another on-campus event, conference, or seminar series. Awardees’ invited guests are experts in either mathematical data science or data science engineering.

Data Science Speaker Travel 2020 Awards

- Betsy DiSalvo (IC): Data Work Civic Engagement Panel

- Diyi Yang (IC): Natural Language Processing/Computational Social Science Seminar

May. 22, 2020

Recently, several Georgia Tech students participating in the Georgia Tech Master of Science in Supply Chain Engineering (MS SCE) program earned LLamasoft's Supply Chain Design - Level 1 (SCD-1) Credential.

Holders of the software neutral, professional credential demonstrate fundamental knowledge of core concepts of supply chain management; basic principles of optimization, simulation, and heuristics; and common practices in data transformation, modeling, analysis, and visualization. The SCD-1 exam is a 50-question multiple choice exam administered during a proctored 90-minute session. The minimum passing score is 80%.

SCL would like to thank LLamasoft for engaging students and faculty through use of its software and creation of the SCD Credential.

SCD-1 Credential Awardee Listing

- Joseph Anthony Marques

- Yogesh M Avhad

- Justin Betancourt

- Anirudhdha Chandrashekar

- Neerajsai Chandrashekar

- Kuldeep Chouhan

- Manuel Ricardo De Juan-Viscasillas

- Talia L Debenedictis

- Ashish Gupta

- Anish Gupta

- Sunadh Hegde

- Chengqi Huang

- Pallav A Jain

- Petrus Stephanus Jansen Van Rensburg

- Ayush Kumar

- Yahan Liu

- Yiguo Liu

- Adhitthyen Muthuswami Rangaswamy Kumar

- Shubham Patil

- Mukul Raghav

- Hrishikesh Ranganah

- Harshit Sabloke

- Fan Scarafoni

- Nakul J Sheth

- Jerin Varghese

For additional information relating to earning the SCD-1 Credential, please visit https://llamasoft.com/company/services/supply-chain-credential/.

News Contact

Please see LLamasoft Supply Chain Credential website.

May. 10, 2020

As the world contemplates ending a massive lockdown implemented in response to COVID-19, Vinod Singhal is considering what will happen when we hit the play button and the engines that drive industry and trade squeal back to life again.

Singhal, who studies operations strategy and supply chain management at the Georgia Institute of Technology, has a few ideas on how to ease the transition to the new reality. But this pandemic makes it hard to predict what that reality will be.

“We know pandemics can disrupt supply chains, because we’ve had the SARS experience, but this is something very different,” said Singhal, the Charles W. Brady Chair Professor of Operations Management at the Scheller College of Business, recalling the SARS viral pandemic of 2002 to 2003. But that event did not have nearly the deadly, worldwide reach of COVID-19.

“There is really nothing to compare this pandemic to,” he said. “And predicting or estimating stock prices is simply impossible, unlike supply chain disruptions caused by a company’s own fault, or a natural disaster, like the earthquake in Japan.”

For more coverage of Georgia Tech’s response to the coronavirus pandemic, please visit our Responding to COVID-19 page.

The earthquake that shook northeastern Japan in March 2011 unleashed a devastating and deadly tsunami that caused a meltdown at a nuclear power plant, and also rocked the world economy. It was called the most significant disruption ever of global supply chains. Singhal co-authored a study on the aftereffects, “Stock Market Reaction to Supply Chain Disruptions from the 2011 Great East Japan Earthquake,” published online in August 2019 in the journal Manufacturing & Service Operations Management.

But COVID-19 represents a new kind of mystery when it comes to something as complex and critical to the world’s economy as the global supply chain, for a number of reasons that Singhal highlighted:

- The global spread of the virus and duration of the pandemic. “We have no idea when it will be under control and whether it will resurface,” Singhal said. “With a natural disaster you can kind of predict that if we put in some effort, within a few months we can get back to normal. But here there is a lot of uncertainty.”

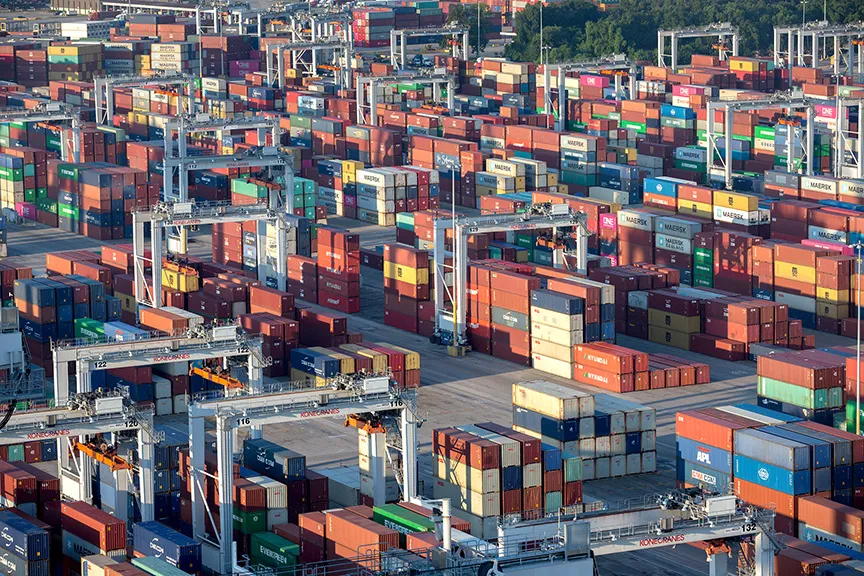

- Both the demand and supply side of the global supply chain are disrupted. “We’re not only seeing a lot of factories shutting down, which affects the supply side, but there are restrictions on demand, too, because you can’t just go out and shop like you used to, at least for the time being,” he said. “And all this is taking place in an environment where supply chains are fairly complex – intricate, interconnected, interdependent, and global.”

- Longer lead times. “We get close to a trillion dollars of products annually from Asian countries, about $500 billion from China,” Singhal said. “Most are shipped by sea which requires a four-to-six-week lead time. The fact that logistics and distribution has been disrupted and needs to ramp up again will increase lead time. So, it will take time to fill up the pipeline, and that is going to be an issue.”

- Supply chains have little slack, and little spare inventory. While manufacturing giants such as Apple, Boeing, and General Motors have more financial slack to carry them through a massive economic belt tightening, their suppliers, spread out across the globe, come in different sizes, different tiers, “and these smaller companies don’t have much financial slack,” said Singhal, pointing to a report of small and medium sized companies in China, “which have less than three months of cash. They’ve already been shut down for two months, and cash tends to go away quickly.

“Many of these companies may go bankrupt,” he added. “So we need to figure out how to reduce the number of bankruptcies. Government is going to play an important role in this, and the stimulus package the U.S. has approved will be helpful.”

Trying to get a handle on how stock markets are responding to all that has happened is like trying to take aim at a moving target during a stiff wind. Volatility has increased significantly since February 13, when the Dow Jones index reached an all-time high of about 29,500.

“That’s because we did not expect the pandemic to spread and disruptions initially were low because of pipeline inventory,” Singhal said, noting that since then the Index dropped sharply, to 18,500 on March 23 (a decline of nearly 38 percent), it picked up and was back to 22,000 by March 30. “The same is true of other stock markets. The Chinese stock market was down 13 percent, but they seem to have the pandemic under control.”

While COVID-19 is making it difficult to predict what the market will look like, Singhal has some ideas of which industries will be most affected.

“Travel, tourism, entertainment, restaurants – businesses that rely on people going out—will take a long time to recover, in terms of profitability and stock price, even once the pandemic is contained,” he said. “People are going to be hesitant to travel after all this. Tourism will take a hit.”

Essentials like groceries are surging as people stock up in reaction to being shut in, but this isn’t a long-term trend. Singhal doesn’t expect this trend to continue as shopping habits and store shelves eventually normalize.

Companies that sell basics, with a strong online presence, will do well, “but industries like automobiles and electronics, which have global supply chains and have a hard time replacing specialized, high-tech components will be affected,” said Singhal, who also has suggestions on the most important issues to address and how to help speed up the recovery and bring supply chains back to normal (or whatever normal looks like after this):

- The ability to bring capacity online, especially for small and medium-sized companies. “Facilities and equipment may need some time to restart,” he said. “Staffing is a big issue. How quickly can you get people back to work? Also, can you get the raw materials and build up the inventory to support production? That may be tough when pent up demand is being released and everybody is competing for limited supplies.”

- Distribution. Lead times already are long, he notes, and a sudden increase in demand for logistics and distribution services as everybody ramps up again could extend lead times.

- Prevent bankruptcies. Government programs need to be established (like the U.S. stimulus package) to keep small- and medium-sized firms in business. This concern extends to second- and third-tier suppliers, and large firms like Apple or Boeing or GM, should do the same for their most critical suppliers.

- Build slack. “Preserve cash, get new lines of credit or draw down lines of credit, maybe cut dividends or stock repurchases,” Singhal said. “And build inventories of critical components.”

Singhal also stresses the need for transparency, up and down the supply chain: “What that means is, companies need to have a good understanding of what is happening to their customers and suppliers, but not just their immediate, first tier customers and suppliers, but also their customers and suppliers, and so on up and down the line.”

It will be very important going forward for the next several months to monitor the health of the supply chain from both the customer perspective and a supplier perspective, because this is a new world, says Singhal, who adds an optimistic postscript, “It’s a crisis situation now, but I think we can put it back together.”

Research News

Georgia Institute of Technology

177 North Avenue

Atlanta, Georgia 30332-0181 USA

Media Relations Assistance: John Toon (404-894-6986) (jtoon@gatech.edu).

Writer: Jerry Grillo

News Contact

John Toon

Research News

(404) 894-6986

Pagination

- Previous page

- 22 Page 22

- Next page