Aug. 09, 2024

A research group is calling for internet and social media moderators to strengthen their detection and intervention protocols for violent speech.

Their study of language detection software found that algorithms struggle to differentiate anti-Asian violence-provoking speech from general hate speech. Left unchecked, threats of violence online can go unnoticed and turn into real-world attacks.

Researchers from Georgia Tech and the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) teamed together in the study. They made their discovery while testing natural language processing (NLP) models trained on data they crowdsourced from Asian communities.

“The Covid-19 pandemic brought attention to how dangerous violence-provoking speech can be. There was a clear increase in reports of anti-Asian violence and hate crimes,” said Gaurav Verma, a Georgia Tech Ph.D. candidate who led the study.

“Such speech is often amplified on social platforms, which in turn fuels anti-Asian sentiments and attacks.”

Violence-provoking speech differs from more commonly studied forms of harmful speech, like hate speech. While hate speech denigrates or insults a group, violence-provoking speech implicitly or explicitly encourages violence against targeted communities.

Humans can define and characterize violent speech as a subset of hateful speech. However, computer models struggle to tell the difference due to subtle cues and implications in language.

The researchers tested five different NLP classifiers and analyzed their F1 score, which measures a model's performance. The classifiers reported a 0.89 score for detecting hate speech, while detecting violence-provoking speech was only 0.69. This contrast highlights the notable gap between these tools and their accuracy and reliability.

The study stresses the importance of developing more refined methods for detecting violence-provoking speech. Internet misinformation and inflammatory rhetoric escalate tensions that lead to real-world violence.

The Covid-19 pandemic exemplified how public health crises intensify this behavior, helping inspire the study. The group cited that anti-Asian crime across the U.S. increased by 339% in 2021 due to malicious content blaming Asians for the virus.

The researchers believe their findings show the effectiveness of community-centric approaches to problems dealing with harmful speech. These approaches would enable informed decision-making between policymakers, targeted communities, and developers of online platforms.

Along with stronger models for detecting violence-provoking speech, the group discusses a direct solution: a tiered penalty system on online platforms. Tiered systems align penalties with severity of offenses, acting as both deterrent and intervention to different levels of harmful speech.

“We believe that we cannot tackle a problem that affects a community without involving people who are directly impacted,” said Jiawei Zhou, a Ph.D. student who studies human-centered computing at Georgia Tech.

“By collaborating with experts and community members, we ensure our research builds on front-line efforts to combat violence-provoking speech while remaining rooted in real experiences and needs of the targeted community.”

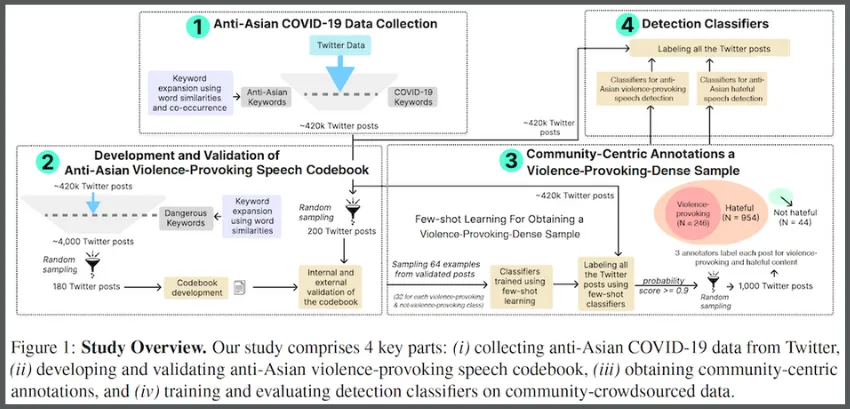

The researchers trained their tested NLP classifiers on a dataset crowdsourced from a survey of 120 participants who self-identified as Asian community members. In the survey, the participants labeled 1,000 posts from X (formerly Twitter) as containing either violence-provoking speech, hateful speech, or neither.

Since characterizing violence-provoking speech is not universal, the researchers created a specialized codebook for survey participants. The participants studied the codebook before their survey and used an abridged version while labeling.

To create the codebook, the group used an initial set of anti-Asian keywords to scan posts on X from January 2020 to February 2023. This tactic yielded 420,000 posts containing harmful, anti-Asian language.

The researchers then filtered the batch through new keywords and phrases. This refined the sample to 4,000 posts that potentially contained violence-provoking content. Keywords and phrases were added to the codebook while the filtered posts were used in the labeling survey.

The team used discussion and pilot testing to validate its codebook. During trial testing, pilots labeled 100 Twitter posts to ensure the sound design of the Asian community survey. The group also sent the codebook to the ADL for review and incorporated the organization’s feedback.

“One of the major challenges in studying violence-provoking content online is effective data collection and funneling down because most platforms actively moderate and remove overtly hateful and violent material,” said Tech alumnus Rynaa Grover (M.S. CS 2024).

“To address the complexities of this data, we developed an innovative pipeline that deals with the scale of this data in a community-aware manner.”

Emphasis on community input extended into collaboration within Georgia Tech’s College of Computing. Faculty members Srijan Kumar and Munmun De Choudhury oversaw the research that their students spearheaded.

Kumar, an assistant professor in the School of Computational Science and Engineering, advises Verma and Grover. His expertise is in artificial intelligence, data mining, and online safety.

De Choudhury is an associate professor in the School of Interactive Computing and advises Zhou. Their research connects societal mental health and social media interactions.

The Georgia Tech researchers partnered with the ADL, a leading non-governmental organization that combats real-world hate and extremism. ADL researchers Binny Mathew and Jordan Kraemer co-authored the paper.

The group will present its paper at the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics (ACL 2024), which takes place in Bangkok, Thailand, Aug. 11-16

ACL 2024 accepted 40 papers written by Georgia Tech researchers. Of the 12 Georgia Tech faculty who authored papers accepted at the conference, nine are from the College of Computing, including Kumar and De Choudhury.

“It is great to see that the peers and research community recognize the importance of community-centric work that provides grounded insights about the capabilities of leading language models,” Verma said.

“We hope the platform encourages more work that presents community-centered perspectives on important societal problems.”

Visit https://sites.gatech.edu/research/acl-2024/ for news and coverage of Georgia Tech research presented at ACL 2024.

News Contact

Bryant Wine, Communications Officer

bryant.wine@cc.gatech.edu