May. 14, 2024

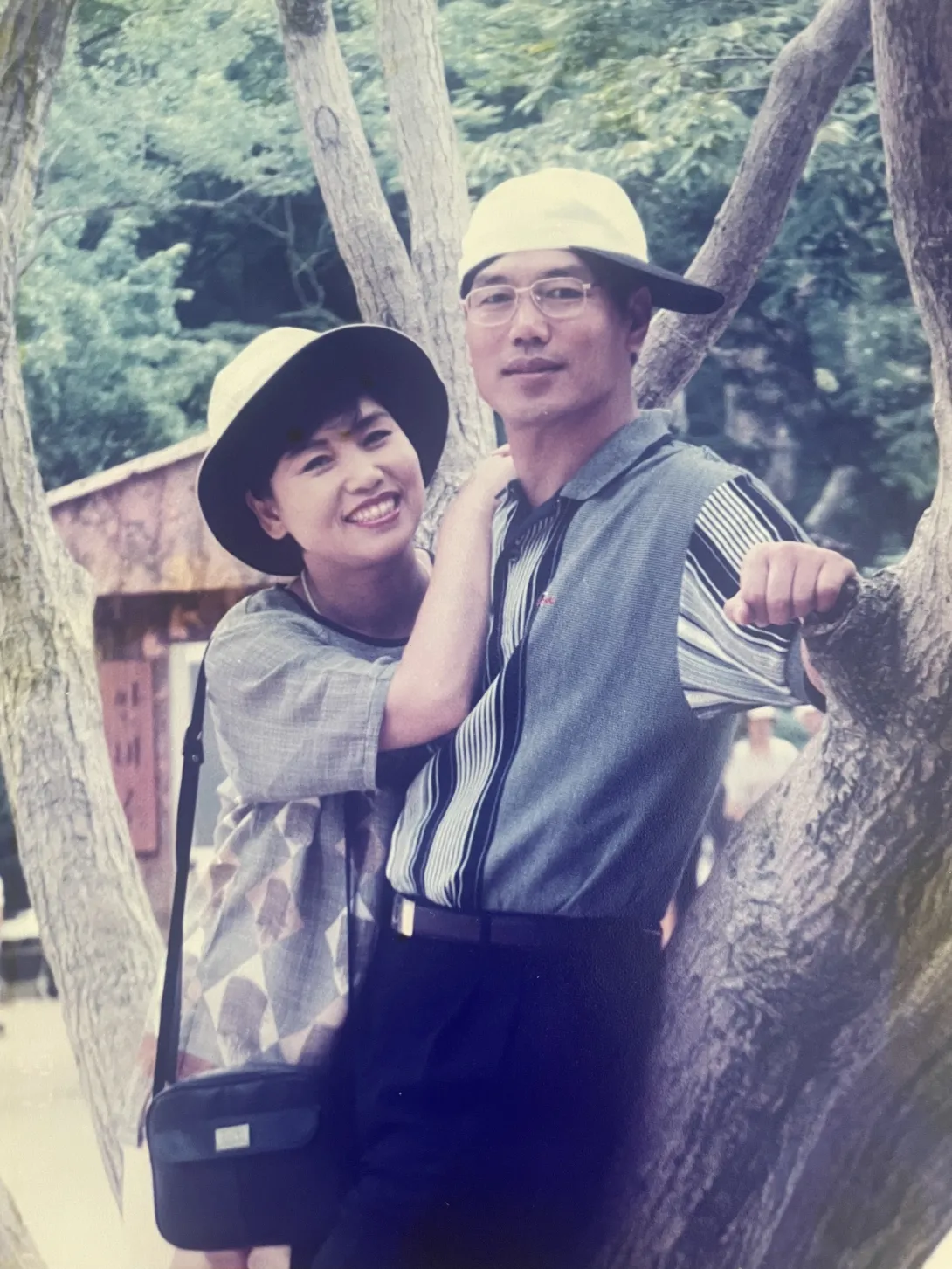

The call from his mom is still vivid 20 years later. Moments this big and this devastating can define lives, and for Hong Yeo, today a Georgia Tech mechanical engineer, this call certainly did. Yeo was a 21-year-old in college studying car design when his mom called to tell him his father had died in his sleep. A heart attack claimed the life of the 49-year-old high school English teacher who had no history of heart trouble and no signs of his growing health threat. For the family, it was a crushing blow that altered each of their paths.

“It was an uncertain time for all of us,” said Yeo. “This loss changed my focus.”

For Yeo, thoughts and dreams of designing cars for Hyundai in Korea turned instead toward medicine. The shock of his father going from no signs of illness to gone forever developed into a quest for medical answers that might keep other families from experiencing the pain and loss his family did — or at least making it less likely to happen.

Yeo’s own research and schooling in college pointed out a big problem when it comes to issues with sleep and how our bodies’ systems perform — data. He became determined to invent a way to give medical doctors better information that would allow them to spot a problem like his father’s before it became life-threatening.

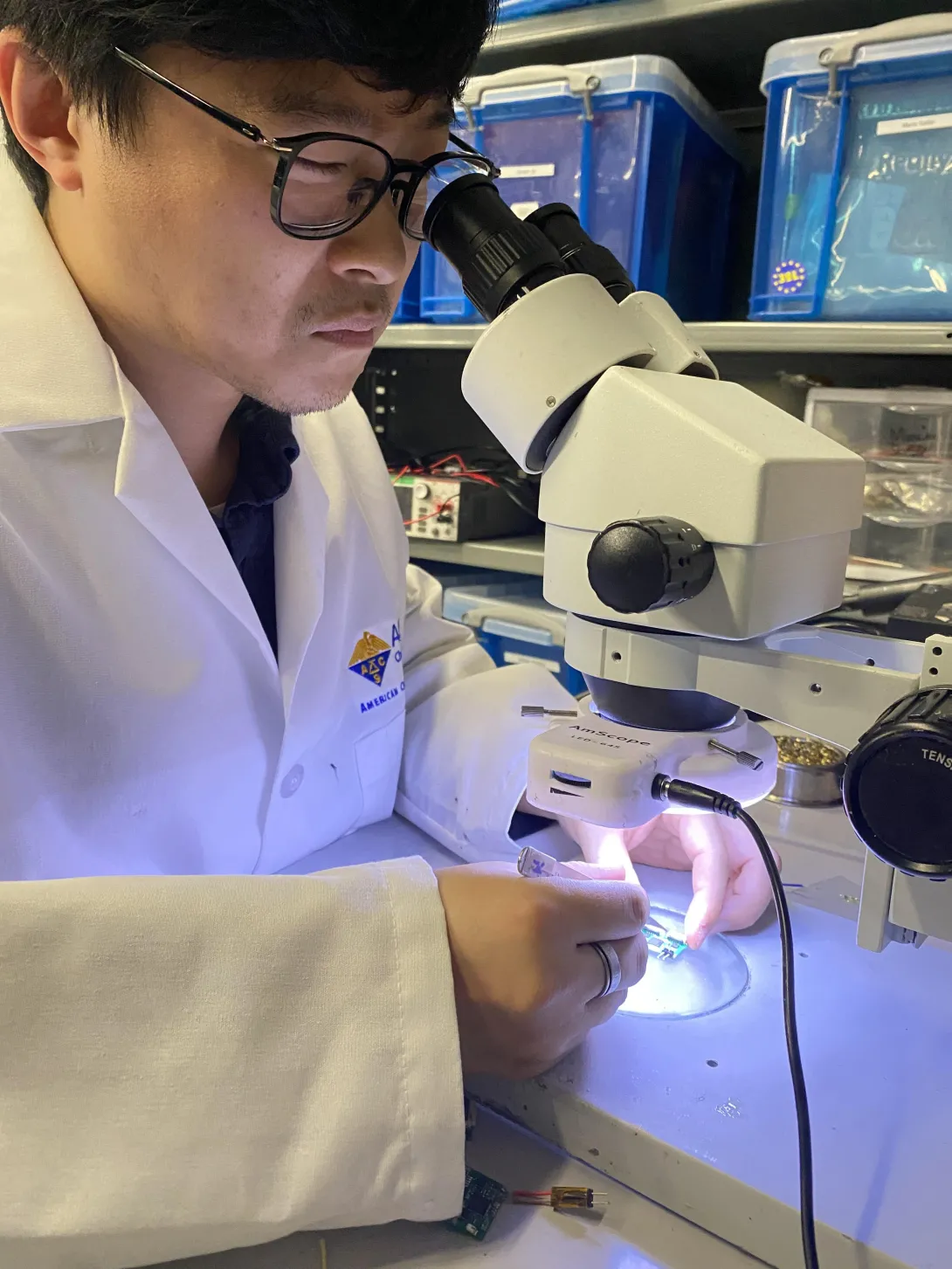

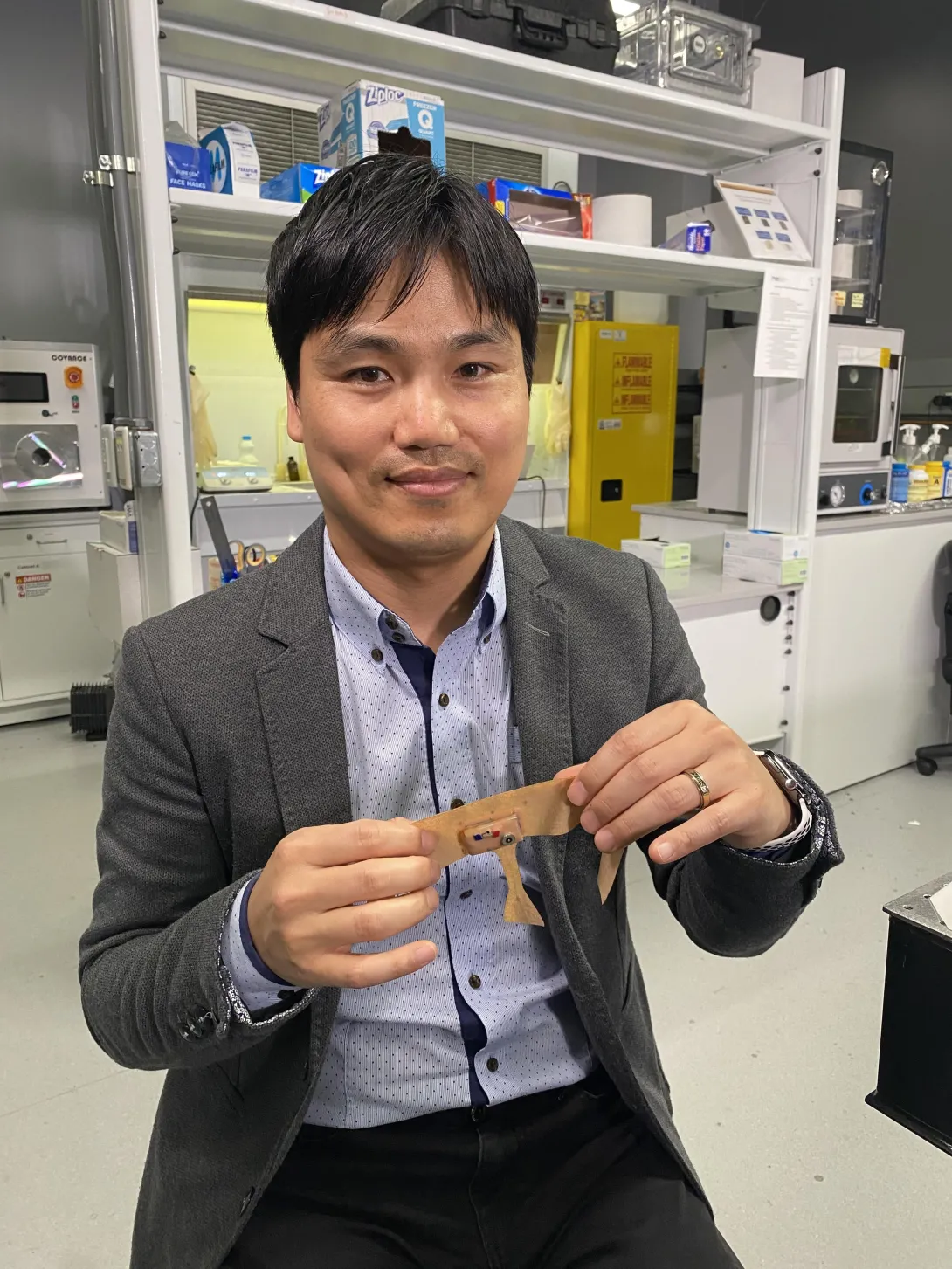

His answer: a type of wearable sleep data system. Now very close to being commercially available, Yeo’s device comes after years of working on the materials and electronics for an easy-to-wear, comfortable mask that can gather data about sleep over multiple days or even weeks, allowing doctors to catch sporadic heart problems or other issues. Different from some of the bulky devices with straps and cords currently available for at-home heart monitoring, it offers the bonuses of ease of use and comfort, ensuring little to no alteration to users’ bedtime routine or wear. This means researchers can collect data from sleep patterns that are as close to normal sleep as possible.

“Most of the time now, gathering sleep data means the patient must come to a lab or hospital for sleep monitoring. Of course, it’s less comfortable than home, and the devices patients must wear make it even less so. Also, the process is expensive, so it’s rare to get multiple nights of data,” says Audrey Duarte, University of Texas human memory researcher.

Duarte has been working with Yeo on this system for more than 10 years. She says there are so many mental and physical health outcomes tied to sleep that good, long-term data has the potential to have tremendous impact.

“The results we’ve seen are incredibly encouraging, related to many things —from heart issues to areas I study more closely like memory and Alzheimer’s,” said Duarte.

Yeo’s device may not have caught the arrhythmia that caused his father’s heart attack, but nights or weeks of data would have made effective medical intervention much more likely.

Inspired by his own family’s loss, Yeo’s life’s work has become a tool of hope for others.