Jul. 29, 2011

It’s achicken and egg question. Where do the infectious protein particles calledprions come from? Essentially clumps of misfolded proteins, prions causeneurodegenerative disorders, such as mad cow/Creutzfeldt-Jakob disease, inhumans and animals. Research in fungi has suggested that sometimes prions can alsohelp cells adapt to different conditions. Prions trigger the misfolding andaggregation of their properly folded protein counterparts, but they usuallyneed some kind of “seed” to get started.

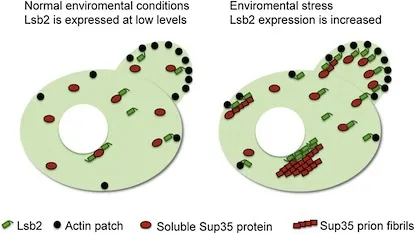

Scientistshave studied a yeast protein called Lsb2 that can promote spontaneous prionformation. This unstable, short-lived protein is strongly induced by cellularstresses such as heat. Lsb2’s properties also illustrate how cells havedeveloped ways to control and regulate prion formation. The results arepublished in the July 22 issue of the journal Molecular Cell.

Thestudy was conducted by members of the Center for Nanobiology of the MacromolecularAssembly Disorders (NanoMAD) which is made up of scientists from the GeorgiaInstitute of Technology and Emory University. Scientists from the NationalInstitues of Health and the University of Illinois at Chicago also contributedto the study. The first author is senior associate Tatiana Chernova, PhD atEmory.

Theaggregated, or amyloid, forms of proteins connected with several otherneurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s and Huntington’scan, in some circumstances, act like prions. So the findings provide insightinto how the ways that cells deal with stress might lead to poisonous proteinaggregation in human diseases.

“Adirect human homolog of Lsb2 doesn’t exist, but there may be a protein thatperforms the same function,” said Keith Wilkinson, professor of biochemistry atEmory University School of Medicine. “The mechanism may say more about othertypes of protein aggregates than about classical prions in humans. Thismechanism of seeding and growth may be more important for aggregate formationin diseases such as Huntington’s.”

Lsb2does not appear to form stable prions by itself. Rather, it seems to bind toand encourage the aggregation of another protein, Sup35, which does formprions.

“Ourmodel is that stress induces high levels of Lsb2, which allows the accumulationof misfolded prion proteins,” Wilkinson said. “Lsb2 protects enough of thesenewborn prion particles from the quality control machinery for a few of them toget out.”

Incontinuation of previous research by Yury Chernoff, director of NanoMAD andprofessor in the School of Biology at Georgia Tech, the new data also show thatin addition to promoting new prions, Lsb2 strengthens existing prions duringstress.

"Littleis known about physiological and environmental conditions influencing amyloiddiseases in humans," said Chernoff. "Therefore, prophylacticmeasures, which could end up being more effective than therapies, areessentially non-existant. We hope that yeast model will help to fill thisgap."

Theresearch was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

Writtenby: Emory University and the Georgia Institute of Technology

News Contact

David Terraso

Georgia Tech College of Sciences

404-385-1393